LITERATURE OF THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

The seventeenth century has gone down in Russian history as an age of revolt. Between the Time of Troubles and 1698, the year of the last revolt by the Streltsy,[1] there were several large-scale popular uprisings, and many minor ones. They were particularly strong and frequent in the middle and latter half of the century. In fifty years Russia witnessed the uprisings of 1648-1650 inMoscow, Novgorod and Pskov, the “copper revolt” of 1662, the peasant war led by Stepan Razin, the rebellion of the Solovetsky Monastery in 1668-1676, and the famous Khovanshchina of 1682, when the Streltsy rebelled and held Moscow for practically a whole summer.

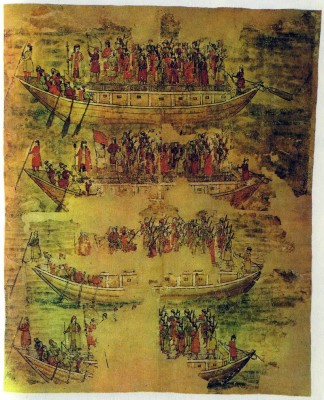

The Campaign by the Moscow Streltsy Against Stepan Razin. Detail of a scroll. 1670s.State Public Library, Leningrad

These revolts, which reflected the insoluble social contradictions of pre-Petrine Russia, compelled the government to introduce half-hearted reforms. The reforms were invariably in the interests of the upper estates and, therefore, in the final analysis merely aggravated the social ills. In response to the Moscow uprising of 1648 the famous Code of 1649 was introduced, a collection of laws passed quickly by the National Assembly and printed by the Moscow Printing House. The Code gave certain rights to the urban middle strata (the strata that had revolted in 1648). It made the tradesfolk a privileged estate. But most of all it benefited the nobility, against whom the revolt had been directed. The estates which the service gentry had previously held for their lifetime only were turned into hereditary holdings which they could bequeath, and the peasants were bound once and for all to the land. The period during which fugitive peasants could be brought back to their masters was no longer limited as before. This intensification of oppression immediately produced peasant revolts. Thus the revolts produced reforms, and the reforms fresh revolts.

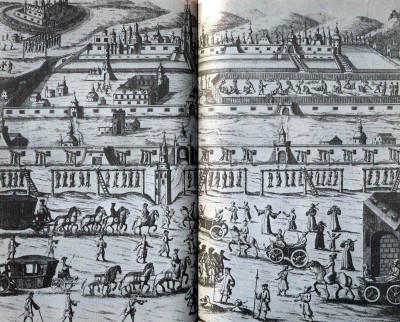

The Execution of the Rebellious Streltsy in Moscow in 1698. Engraving from the Vienna edition of Johann Korb’s Diary. C. 1700. Academy of Sciences Library, Leningrad

Russian culture of the seventeenth century was also a culture of “revolt”, that had lost the external unity and monolithic quality characteristic of the Middle Ages. Culture split into several trends, either autonomous or directly opposed. The greatest blow to cultural unity was dealt in the 1650s by the church reforms of Patriarch Nikon, who introduced many changes into liturgical practice and ritual, in particular, the Creed, the number of fingers used in making the sign of the cross, etc. This led to a Schism in the Russian Orthodox Church; historians reckon that between a quarter and a third of the population remained true to the old rites. Those who did not accept Nikon’s reforms and adhered to the pre-reform, “old” rules and customs became called the Old Believers. The Old Believers constituted the most powerful religious movement in the whole of Russian history.

On the eve of Nikon’s reforms the Church was experiencing a profound crisis. The bishoprics and monasteries (whose serfs constituted eight per cent of the population of Russia) had accumulated great wealth, whereas the lower ranks of the clergy, the country parish priests, subsided in poverty and ignorance. All educated and thinking people realised that the Church needed reform. The idea of transforming church life inspired the movement of the God-lovers, which reached its height in the first seven years of the reign of Tsar Alexis, son of Michael, who came to the throne in 1645. This was a revolt of the lower ranks of the clergy against the bishops, of the parish priests, who in terms of possessions and way of life did not differ greatly from the urban tradesmen and artisans or even the peasants.

The God-lovers’ preaching contained a strong social element, in Christian attire, of course. The God-lovers did not urge people to enter hermitages and monasteries. They offered “salvation in the world”, set up schools and almshouses, preaching in churches and in the streets and squares.

This social element links the God-lovers’ movement with the Reformation in Western Europe. Yet there was also a great difference between them. For the God-lovers, the zealots of the old belief, the transformation of the Church meant the total subjection of Russian life to the Church. They saw the church during a service as the living embodiment of the kingdom of heaven on earth. The imaginary “holy Russia”, for the return of which they fought so passionately, was envisaged by them in the likeness of a church where pious souls communed with the Lord. For this reason the reforming of the liturgy was a matter of special concern to both the future Patriarch Nikon and the Archpriest Avvakum, who at first worked side by side in the God-lovers’ movement, but later became sworn enemies. This external, ritual aspect greatly influenced the Schism in the middle of the century.

When Nikon, a personal friend of the young Tsar Alexis, was made patriarch, it transpired that he had a totally different understanding of the subjection of life to the Church from his recent allies. The latter saw Russia as the last bulwark of “immaculate” Orthodoxy and sought to protect it from foreign influence. They looked with suspicion on Orthodox Greeks, Ukrainians and Byelorussians, convinced that under the rule of Turks and Poles these people could not have preserved their faith intact. Nikon, however, opposed isolationism and dreamed of Russia leading world Orthodoxy. He firmly supported the attempts of Bogdan Khmelnitsky to join the Ukraine to Russia, although he realised that this would inevitably involve war with Poland. He dreamed of the liberation of the Balkan Slavs, and even dared to think of conquering the “second Rome”, once Constantinople, now Istanbul.

It was this idea of a world Orthodox empire under the aegis of Russia that led to the reform of the Church. Nikon was worried about the differences between Russian and Greek rites, which he regarded as an obstacle to Moscow’s supremacy. So he decided to standardise ritual taking as a basis Greek practice, which had recently been introduced in the Ukraine and Byelorussia. Just before Lent in 1653 the Patriarch sent a “memorandum” to all the Moscow churches prescribing the use of three fingers instead of two for making the sign of the cross. Then followed the revision of liturgical texts. Those who refused to accept the changes were excommunicated, exiled, imprisoned or executed. The Schism had begun.

In preferring seventeenth-century Greek ritual, Nikon was proceeding from the belief that the Russians, who adopted Christianity from Byzantium, had themselves distorted this ritual. History has proved him to be wrong. During the reign of St Vladimir the Greek Church used two different sets of rules, the Studion and the Jerusalem rules. Russia adopted the Studion rules (prescribing two fingers) which were completely ousted with the time in Byzantium by the Jerusalem rules.

Like Nikon, the zealots of the old belief were also poor historians (although in the dispute concerning ritual they were right). It was not the desire for historical truth, but offended national pride that led them to oppose the reforms. They regarded the break with age-old tradition as a violation of Russian culture. They detected the Westernising tendencies in Nikon’s reforms, and protested against them, fearing to lose their national distinctiveness. The very idea of reforming Orthodoxy smacked of Westernising to the God-lovers.

The imperious and harsh Nikon had no trouble in removing the God-lovers from the helm of the Church. But his victory was short-lived. His claims to unlimited power angered the tsar and boyars. By 1658 the differences were so acute that Nikon suddenly vacated the patriarchal throne. He spent eight years in his New Jerusalem Monastery, until the Church Council of 1666-1667 pronounced sentence on him and the leaders of the Old Believers, at the same time as approving his reforms.

The nobility supported the reforms for various reasons. The reforms promoted the ideological and cultural drawing together of Russia and the Ukraine which had recently joined Russia. The nobility did not want the subjection of Russian life to the Church in the form advocated by the God-lovers or by Nikon, who believed that “the Church is higher than the State”. On the contrary, the nobility’s ideal was restriction of the rights and privileges of the Church and secularisation of life and culture, without which Russia as a European power could not hope for progress, an ideal later embodied in the activity of Peter the Great. In this connection it is indicative that the nobility barely played any part in defending the old beliefs. The few exceptions (the boyar’s wife Fedosia Morozova and Prince Khovansky) merely prove the rule.

It was only natural, therefore, that the Old Believers’ movement very quickly turned into a movement of the lower classes, the peasants, Streltsy, Cossacks, poorer artisans and tradespeople, lower ranks of the clergy, and a section of the merchants. It produced its own ideologists and writers who combined criticism of reforms and defence of the national past with dislike of the whole policy of the tsar and the nobility and even went as far as calling the tsar Anti-Christ.

So the upper classes of Russian society chose the path of Europeanisation, the path of reorganising the cultural system inherited from the Middle Ages. The purpose and form of this reorganisation was understood differently by the different groups of thinkers of that day; hence the “vacillation” among the upper strata continued. Already at the Church Council of 1666-1667 two hostile parties emerged, the Graecophile (“Old Muscovite”) and Westerniser (“Latiniser”) parties. The former was led by the Ukrainian Epiphanius Slavinetsky, and the latter by the Byelorussian Simeon of Polotsk, both pupils of the Kievan school. But Epiphanius studied at this school before Metropolitan Peter Mogila gave it a Latin trend, basing it on the Polish Jesuit collegia. Simeon of Polotsk, however, was educated as a devoted Latinist scholar and Polonophile. Both parties agreed that Russia needed enlightenment, but set themselves different tasks.

Epiphanius Slavinetsky and his followers enriched Russian letters with numerous translations, including dictionaries and medical textbooks. But for writers of this type enlightenment was merely the quantitative accumulation of knowledge. They did not entertain the thought of a qualitative reorganisation of culture, believing that it was dangerous to break with national traditions. The “Latinisers” and Simeon of Polotsk, however, made a firm break with this tradition. They sought their cultural ideal in Western Europe, above all in Poland. It was the “Latinisers” who first transplanted to Russian soil the great European style of the Baroque in its Polish version adapted to Muscovite conditions. It was with the “Latinisers” that disputes began in Russia—literary, aesthetic and historico-philosophical debates.

It was the “Latinisers” who created the professional community of writers in Moscow. For all the differences in the individual biographies of the members of this literary fraternity, it produced a special type of writer fashioned on the Ukrainian-Polish model. The professional writer engaged in pedagogical pursuits, who collected an extensive private library, took part in publishing ventures, studied foreign authors and knew at least two foreign languages, Latin and Polish. He regarded writing as his main pursuit in life.

After the death of Epiphanius Slavinetsky and Simeon of Polotsk, during the regency of Sophia (1682-1689), there was an open clash between the “Latinisers” and Graecophils. The latter emerged victorious with the support of Patriarch Joachim. They managed to gain control of Moscow’s first establishment of higher education, the Slavonic-Graeco-LatinAcademy, founded in 1686.

After Sophia was overthrown they succeeded in sending the leader of the “Latinisers”, the poet Sylvester Medvedev, to the scaffold. This victory did not put an end to professional literature, however. Professional writing was now firmly established in Russia.

The percentage of authorial works rose sharply in seventeenth-century literature. The anonymous stream that reigned supreme in the Middle Ages did not dry up. But whereas during that period the anonymity or, at least, the playing down of the personal element was characteristic of all literary production in general, now it was primarily fiction that was anonymous, while poetry, rhetoric and publicistics bore the name of the author. The anonymous stream was nourished, in particular, by links with Western Europe. From there Muscovy received all manner of entertaining “popular books”, cheap, mass-produced publications. The stream of fiction in the seventeenth century was spontaneous and uncontrollable. Anonymous works of fiction showed the same artistic and ideological diversity as authorial works. The links with Europe produced the translated tales of chivalry and novella. The first original works in these genres also appeared, as, for example, The Tale of Vasily the Golden-Haired and The Tale of Frol Skobeyev.

A reassessment of the traditional genre schemes led to the creation of qualitatively new, complex compositions, such as The Tale of Savva Grudtsyn with its Faustian theme. The artistic treatment of history is reflected in the cycle of stories about the founding of Moscow and the tale of the Page Monastery in Tver.

The social basis of literature was constantly expanding. The democratic literature of the lower strata of society was beginning to appear. These strata, the poor clergy, the street scribes and the literate peasants, spoke out in the independent and free language of parody and satire.

[1] Streltsy—members of a military corps instituted by Ivan IV, who enjoyed special privileges in the MuscoviteState in the 16th and 17th centuries.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature