Epiphanius the Most Wise

Epiphanius was born in Rostov in the first half of the fourteenth century. In 1379 he became a monk in a Rostov monastery. Later he moved to the Trinity Monastery of St Sergius. He visited Jerusalem and Mount Athos and most probably travelled in the Orient. He died in the 1420s. Because of his erudition and literary skill he became known as “the Most Wise”. Two vitae belong to his pen: The Life of St Stephen of Perm, written in 1396-1398, and The Life of St Sergius of Radonezh, written between 1417 and 1418.

In the author’s foreword to The Life of Metropolitan Peter, as already mentioned, Cyprian says that the vita was to serve as an embellishment for the saint. Epiphanius’ Life of St Stephen of Perm is a fine example of the vita embellishment, the eulogy to a saint.

In this work Epiphanius’ views on the literary tasks of the hagiographer are reflected most fully and clearly. Ordinary words are incapable of expressing the greatness of the deeds done by holy men to the glory of Christ, but the author of a story about a saint is a common mortal. And so, appealing to God for help and relying on the protection of the saint whom he is extolling, the hagiographer strives to use the ordinary devices of language so as to make the reader see the saint as a person of a completely different spiritual type from other people. Therefore linguistic artifice is not an aim in itself but a device with the help of which the author is able to extol the hero of his narrative in worthy fashion.

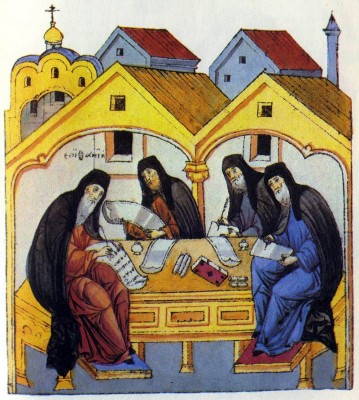

Epiphanius the Most Wise Compiling the Life of St Sergius оf St. Sergius Radonezh. 16th-century illumination. State Lenin Library, Moscow

At the beginning of the vita (and this is particularly characteristic of works in the panegyric style) the author speaks of his literary talents in the most self-denigrating terms. In one such tirade he writes that he is “coarse of mind” and thick of tongue, that he is not versed in rhetoric, philosophy, or bookish wisdom, the “braiding of words” and, to put it simply, he is full of ignorance.27 The author’s professed lack of learning and ignorance contradict the rest of the text, in which his erudition and ability to use the devices of rhetoric manifest themselves fully. This is a clever literary device with the same aim, that of praising and extolling the saint. If the author of a vita, whose writing showed him to be highly learned and a master of the art of rhetoric, never tired of saying how worthless he was, the person who read or heard the vita was bound to feel even more worthless before the saint’s greatness. Moreover the author’s confession of his ignorance and literary inability which contradicted the actual text was intended to create the impression that what he had written was a kind of Divine revelation, inspiration from on high.

In The Life of St Stephen of Perm Epiphanius achieves true virtuosity in his eulogy of Stephen. His selection of poetic devices and the compositional structure of the text are a well-planned, carefully elaborated literary system.28 In his writing the traditional poetic devices of mediaeval hagiography are made more complex and enriched with new shades. The frequent use of amplification, the strings of similes and metaphors, the speech rhythms, and assonance make the text very moving and expressive.

Epiphanius on several occasions defines the nature of the writer’s work as the “braiding of words”. This definition conveys very well the ornamental nature and verbal refinement of Epiphanius’ style and the expressive-emotional style in general.

The “braiding” of the eulogy to the saint is the main purpose of The Life of St Stephen of Perm. Nevertheless this eulogy to the missionary of the Perm lands also contains lifelike sketches and historical facts. These are particularly evident in the descriptions of the ordinary life of the people of Perm, the stories about their idols and their hunting skill, and Epiphanius’ discourses on the relations between Moscow and Perm. The long central section of the Life, the story of Stephen’s struggle against the Perm magician Pam, is like an adventure story full of vivid sketches and lively scenes.

Embroidered cloth on the tomb of St Sergius of Radonezh. 1424. Zagorsk State Museum-Preserve of History and Art

Epiphanius’ second work, The Life of St Sergius of Radonezh, is of a more narrative nature than The Life of St Stephen. It is far simpler stylistically and contains more factual material. Many episodes in The Life of St Sergius have a distinctive lyrical quality (the story of the childhood of the boy Bartholomew, who took the name of Sergius when he became a monk, the episode in which Bartholomew’s parents beg him not to enter a monastery until they die, so that he will be able to look after them in their old age, etc.)29

Whereas in The Life of St Stephen of Perm Epiphanius shows himself to be a brilliant stylist, in The Life of St Sergius he appears as a master of the narrative. The Life of St Sergius was extremely popular in mediaeval times and later due largely to Sergius’ remarkable moral qualities which won him great authority in Old Russia (as we know Dmitry Donskoy came to him at the Trinity Monastery before the Battle of Kulikovo for approval of his decision to do battle with Mamai), and has survived in a large number of manuscripts.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature