Tales of Mongol Attacks n Russia After the Battle of Kulikovo. The Tale of Tokhtamysh’s Campaign Against Moscow

The Tale of Tokhtamysh’s Campaign Against Moscow. After Mamai’s defeat at Kulikovo Field Khan Tokhtamysh seized power in the Horde. Realising that the victory over Mamai could mean a radical change in the attitude of the Russian princes to the Horde, Tokhtamysh undertook a campaign against Moscow in 1382. Due to the unconcerted action of the Russian princes, the depletion of the Russian forces as a result of the Battle of Kulikovo and some tactical errors, Moscow was captured by the Mongols and cruelly devastated. After a short time in Moscow, Tokhtamysh returned to the Horde, devastating the principality of Ryazan on the way, although the Prince of Ryazan had assisted Tokhtamysh when his army was advancing on Moscow. Tokhtamysh’s invasion is the subject of a chronicle tale in several versions.

The chronicle of 1408, as we can see from extant chronicles that derive from this compilation (for example, The’ Rogozh Chronicle), contained a short chronicle tale. The compilation of 1448, as can be seen from extant chronicles originating from it (the Novgorod Fourth, Sophia First and a number of others), contained an extended chronicle tale.19

The chronology and correlation of the above-mentioned compilations are such that the short chronicle tale appears to be primary.20 However, the reverse may be the case. In certain parts of the short tale one can detect the condensation of a fuller primary text (i.e., the text of the extended story). The details of Tokhtamysh’s invasion found in the extended chronicle tale and absent in the short one suggest not later inventions, but the testimony of a contemporary or even eyewitness of what is being described. Stylistically the extended tale is a self-contained text. Thus, there are equal grounds for seeing the short story as a condensation of the extended one. That is to say, we can assume that The Tale of Tokhtamysh’s Campaign Against Moscow was created independently of the chronicles and only included in them later: its short form in the compilation of 1408 and its extended form in that of 1448. The short chronicle tale with some rearrangements and slight textual variations is included in full in the extended one.

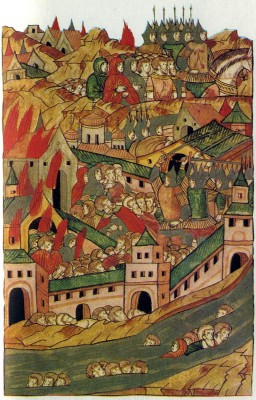

The Capture of Moscow by Khan Tokhtamysh in 1382. Illumination from The Illustrated Chronicle. 16th century. Academy of Sciences Library, Leningrad

The extended tale begins by describing a sign from heaven that “foretold the evil coming of Tokhtamysh to the land of Russia”.21 Tokhtamysh embarks on his campaign against Russia secretly, rapidly and suddenly. In spite of this, the Prince of Moscow learns of it in advance. Dmitry Donskoy does not have time to assemble an army, however, and he leaves Moscow. The town, behind whose stone walls not only Muscovites seek refuge but also the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, waits anxiously for the enemy. For three days the Mongols besiege Moscow to no avail. On the fourth day they assure the Muscovites “with false speeches and false words of peace” that if they come out to greet the khan “with honour and gifts”, they will receive “peace and love” from him. The trick works and the enemy captures the town. After a detailed description of the slaughtering of the inhabitants and the terrible sacking of the town, the author exclaims: “Up till then Moscow had been for all a great city, a wondrous city, a populous city, with many people, many lords, and all manner of riches. And its appearance changed in a single hour, when it was captured, sacked and burnt. There was nothing on which to look, only earth and dust, and remains, and ashes, and many dead bodies, and the holy churches stood in ruins, as if orphaned, as if widowed.”

The extended Tale of Tokhtamysh’s Campaign Against Moscow is a most interesting work of Old Russian literature in which the role of the people in the events that take place is shown in greater detail than in any other work of this period. The story of the siege describes the courageous resistance of the townspeople. The author notes bitterly that they have to face an adversary far better versed in the art of warfare. Here is a description of the skill of the Mongol archers: “Some shot standing, others were taught to shoot at the run, while some shot on horseback at full gallop, right and left, backwards and forwards, never missing.” But among the townspeople unversed in warfare there are some real heroes. The author describes one of them in detail. “A certain Muscovite standing on the Frol Gate,[1] a clothier by the name of Adam, after noticing and picking out a well-known Mongol of high birth, the son of a prince in the Horde, did pull his cross-bow and let fly an arrow unexpectedly, which pierced the Mongol’s cruel heart and brought him a quick death. This grieved all the Mongols sorely, so that even the ruler was sorrowed by what had taken place.”

At the beginning of his account of the siege of Moscow the author gives a vivid description of the events in the town. Following the grand prince, who goes north to muster an army, the most high-ranking boyars hurriedly leave the town and Metropolitan Cyprian also departs. The townspeople try to stop the Metropolitan and the boyars from leaving. The author does not approve of such actions by the common people and says of the latter that they are “rebellious, bad men, seditious folk”. But he does not express any sympathy with the Metropolitan and the boyars who left Moscow, however. The people for whom the unknown author of this work feels most sympathy are the merchants and tradesmen. This can be seen not only from the fact that the hero Adam is a clothier, but from a number of other details as well. At the very beginning of the tale we are told about the fate of the merchants who were visiting the Horde when Tokhtamysh decided to march on Moscow (he had them all imprisoned and their wares confiscated). Speaking of the destruction of Moscow the author mentions that the merchants’ wealth, together with the prince’s treasury and the property of the boyars, was looted. He speaks of himself in the first person: “But Prince Oleg of Ryazan … not wishing us well, but helping his own principality”, “Woe is me! ’Tis terrible to hear, but ’twas more terrible then to see.”

All this gives grounds for assuming that the author was a Muscovite, someone connected with the trading world, who witnessed the events which he describes and did not have to borrow from the chronicle-writing of the prince or the Metropolitan. The vivid narrative combining lively descriptions of real events with rhetorical passages, the stylistic repetitions and contrasts testify to the literary talent of the unknown author of the Tale.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature