The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land

The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land has come down to us in two manuscripts, not as an independent text, but as the foreword to the first redaction of The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky.23

Some specialists believe that The Lay of the Ruin is the introduction to a secular biography of Alexander Nevsky that has not survived. But a comparison of the style of the Lay with that of The Tale of the Life of Alxander Nevsky shows that these works are independent of each other and were written at different times. The linking of these texts occurred later in their literary history. Consequently there are more grounds for seeing The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land as a small fragment of a larger work describing the terrible disaster that befell the Russian lands.24

The names mentioned in the Lay and the context in which they are found (“up to the Yaroslav of our day and his brother Yuri, Prince of Vladimir”), the echoes of the legends about Vladimir Monomachos and certain South-Russian features in the work give grounds for assuming that The Lay of the Ruin was written by an author of South-Russian origin in North-Eastern Russia not later than 1246 (the Yaroslav “of our day” is Yaroslav, son of Vsevolod, and he died on September 30, 1246). The title of the work (which is found in one manuscript) and the phrase on which the text breaks off (“And in those days … a disaster befell Christian folk”) give grounds for regarding this work as a response by an unknown author to the Mongol invasion. Most likely The Lay of the Ruin was written between 1238 and 1246.

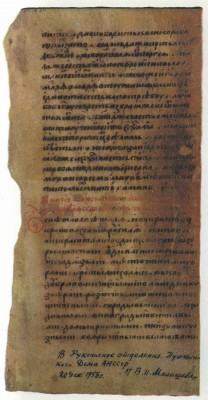

The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land. First page of the manuscript. 16th century. Institute of Russian Literature, Leningrad

The surviving fragment of The Lay of the Ruin, either the foreword to or first part of a work on the “ruin of the Russian land”, is about the horrors of Batu’s invasion and the defeat of the Russian principalities. It gives a moving description of the former beauty and wealth of the Russian land, its former political might. This type of foreword to a text about a country’s sufferings and misfortunes was quite common. It is also found in other works of early and mediaeval literature that contain a eulogy to the greatness and glory of the author’s native land. A specialist who has studied this problem concluded that the Lay “is closer not to all patriotic works in other literatures, but only to those that appeared under similar conditions, when the writer’s homeland was suffering from war, internal strife and arbitrary rule”.25

The author of the Lay extols the beauty and splendour of the Russian land: “Oh, fairest of fair and finely adorned Russian land! You are renowned for many beauties: you are famed for your many lakes, rivers and sacred springs, your mountains and steep hills … your wondrous and diverse birds and beasts…” The Russian land is adorned not only with the beauties and gifts of nature, it is also famed for its “mighty princes, honest boyars, and many nobles”.

Developing the theme of the “dread princes” who have conquered “pagan countries”, the author of the Lay portrays the ideal Russian prince, Vladimir Monomachos, before whom all neighbouring peoples and tribes trembled. Even the Byzantine Emperor Manuel sent Vladimir gifts so that “he would not take Constantinople away from him”. This hyperbolised picture of the “dread” grand prince embodied the idea of strong princely authority and military prowess. At the time of the Mongol invasion and the military defeat of the Russian land a reference to the strength and might of Monomachos served as a reproach to the Russian princes of the day and was also intended to inspire hope for a better future. It is, therefore, no accident that the Lay was inserted at the beginning of The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky; here Alexander, a contemporary of Batu’s, appears as a dread prince.

In its poetic structure and ideology The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land is close to The Lay of Igor’s Host. Both works contain a high degree of patriotism, a strong sense of national awareness, hyperbolisation of the strength and military valour of the warrior prince, a lyrical attitude towards nature, and a rhythmic structure. Both works also combine a lament with a eulogy, a eulogy to the former greatness of the Russian land and a lament at its misfortune in the present. Both works have identical stylistic formulae and poetic images. The nature of the titles is similar. The phrase in The Lay of Igor’s Host from “Vladimir of old to Igor of our own days…” is parallel to the phrase in The Lay of the Ruin “From the great Yaroslav to Vladimir, and to Yaroslav of our day…” The authors of both works frequently use collective names of peoples. Other parallel expressions can also be found.26

The Lay of Igor’s Host was a lyrical call for the unity of the Russian princes and Russian principalities on the eve of the Mongol invasion. The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land is a lyrical response to this invasion.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature