The Lives of SS Boris and Gleb

Examples of the second type of vita, the martyria (the story of a martyred saint), are the Lives written about the death of Boris and Gleb at the hand of their brother Svyatopolk. One of them (The Reading Concerning the Life and Murder of SS Boris and Gleb), like The Life of St Theodosius of the Caves, was written by Nestor.88 The author of the other Life, entitled The Tale and the Passion and the Encomium of the Holy Martyrs Boris and Gleb, is not known. Specialists are divided as to when the Tale was written—in the middle of the eleventh century or the beginning of the twelfth—and, consequently, as to whether it came before or after The Reading Concerning the Life and Murder written by Nestor.89

The creation of the religious cult of Boris and Gleb had two aims. On the one hand, the canonisation of the first Russian saints enhanced the ecclesiastical authority of Russia and testified to the fact that Russia was “favoured before God” and had been blessed with its own saints. On the other hand, the cult of Boris and Gleb was of great political importance: it “sanctified” and affirmed the frequently proclaimed political idea that all the Russian princes were brothers, and also stressed the need for the younger princes to submit to the senior ones.90 This is precisely what Boris and Gleb did: they obeyed their elder brother Svyatopolk unquestioningly, respecting him like a father, and he abused their brotherly obedience.

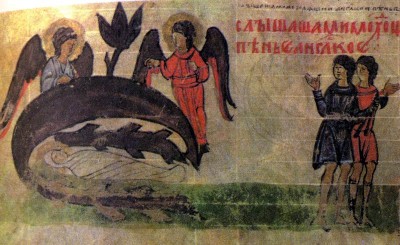

The Tale of the Holy Martyrs Boris and Gleb. The murder of Boris. Illumination from the Sylvester Miscellany. 14th century. Central State Archive of Ancient Documents, Moscow

Let us now examine in more detail the events reflected in the Tale concerning Boris and Gleb. According to the chronicle version (in The Tale of Bygone Years under the entry for 1015), after Vladimir’s death one of his sons, Prince Svyatopolk of Pinsk (some sources give Turov), seized the throne of the grand prince and decided to kill his brothers so as to “hold Russian power” alone.

Svyatopolk’s first victim was Prince Boris of Rostov. Shortly before his death Vladimir had sent him off with his band of warriors to fight the Pechenegs. When Boris received the news of his father’s death, Vladimir’s warriors were ready to take the throne for the young prince by force, but Boris refused, for he did not wish to raise his hand against his elder brother, and declared his readiness to respect him like a father. The warrior band left Boris with nothing but a handful of his own “youths” (young warriors) and he was murdered on Svyatopolk’s orders.

Then Svyatopolk sent a messenger to Prince Gleb of Murom, asking him to make haste to his ailing father. Not suspecting anything, Gleb set off for Kiev. In Smolensk he was overtaken by a messenger from his brother Yaroslav with the terrible news: “Do not go, your father is dead, and your brother murdered by Svyatopolk.” Gleb mourned his father and brother bitterly. And it was here, by Smolensk, that the murderers sent by Svyatopolk found him. On their orders the prince’s cook stabbed him to death.

Yaroslav Vladimirovich entered the struggle against the murderer and did battle with Svyatopolk on the banks of the Dnieper. In the early morning Yaroslav’s men crossed the river and “pushed away their boats from the shore”, so as to fight for victory or death, then fell upon Svyatopolk’s host. In the ensuing battle Svyatopolk was defeated. With the help of King Boleslaw of Poland he managed to drive Yaroslav out of Kiev for a while, but in 1019 Svyatopolk’s men were defeated once more, and he fled the country and died in a remote spot between Poland and Bohemia. The Tale appears to recount the same events, but greatly enhances the hagiographical element. It is characterised by heightened emotions and deliberate conventionality.

Feudal strife was a fairly common phenomenon in the Russia of this period, and the participants in these conflicts usually acted in accordance with self-interest, ambition, military prowess or diplomatic skill; they invariably fought hard in defence of their rights and life. Against this background the meekness of Boris and Gleb, as portrayed by the chronicle account, is unusual, but in the Tale it becomes quite excessive. Thus, having learnt of the attempt about to be made on his life, Boris not only does not think of trying to escape, but, quite the reverse, waits quietly for his fate and prays to God to forgive Svyatopolk the sin of fratricide, thus, as it were, predicting death for himself and for Svyatopolk the successful execution of his foul plan.

The Tale of the Holy Martyrs Boris and Gleb G1eb’s body between Two Boards. Illumination from the Sylvester Miscellany. 14th century. CentralState Archive of Ancient Documents, Moscow

No less unexpected is the behaviour of Gleb. When the murderers leap into his boat with drawn swords and the prince’s time has all but come, he manages to deliver three soliloquies and pray. All this time the murderers wait patiently, with drawn swords poised motionlessly over their victim.

Igor Eremin has drawn attention to another contradiction in the narrative. Boris is encamped by Kiev, but in the Tale it is said three times that he is “on his way” to his brother. Eremin believes that the logic of the narrative led the author to make this discrepancy. True to his duty as a vassal Boris should have gone to Kiev, but he would have seemed to be following the advice of the warrior band, “Go unto Kiev and take your father’s throne”, which did not fit in with his character. So Boris “goes” and stays in the same place at the same time.91 Boris is killed three times. First they strike him with spears through the tent, then they urge one another to “finish what has been ordered” (i.e., murder Boris), when he rushes out of the tent and, finally, we learn that the wounded but still alive Boris is killed by the swords of pursuing Varangians sent by Svyatopolk.

Another characteristic detail. Scholars have drawn attention to the lyrical portrayal of Gleb as “young and defenceless”, who begs his murderers for mercy “like a child” saying, “Let me alone… Let me alone!”92 This is a purely literary device. In fact, if we accept the chronicle story about Vladimir, at the time of his death his youngest son was at least twenty-seven. Boris and Gleb are thought to be his sons from a Bulgarian wife, i.e., they were born when Vladimir was still a pagan. Twenty-seven years elapsed between Vladimir’s conversion and marriage to the Byzantine princess Anna and his death in 1015. Therefore both Boris and Gleb were mature warriors, not youths.

Eremin quotes another example of “involuntary tribute to the genre”: Boris is portrayed in the Tale as a martyr for the faith, although Svyatopolk was not threatening his faith, of course.93

Svyatopolk, on the other hand, personifies the evil that must be present in a vita as the force against which the saint fights successfully or not. Svyatopolk is cruel and cunning and does not try to justify this evil even to himself. On the contrary, he expresses his readiness to “add one unlawful act to another”. He succeeds in killing Boris, Gleb and Svyatoslav, and for a while, in defeating Yaroslav. But Divine retribution is inescapable, and Svyatopolk the Accursed (he bears this name throughout Old Russian literature in which he is invariably the villain) was defeated in a decisive battle and fled, terrified and sick (“his bones grew weak” the chronicler tells us), to die in a remote spot. A vile stench comes from his grave.

In spite of the indisputable tribute to the hagiographical genre, the Tale could not be regarded as a model vita in its depiction of events and particularly its portrayal of the characters. It was too documentary and historical. This, according to Igor Eremin, explains why Nestor decided to write another Life, more in keeping with the strict requirements of a classical canon of this genre.

Nestor’s Reading does indeed contain all the essential elements of a canonical Life: it begins with a lengthy introduction explaining why the author decided to undertake the writing of this Life and a brief account of the history of the world from Adam to the conversion of Russia. In the actual hagiographical part Nestor, as the genre requires, describes the childhood of Boris and Gleb and the piety which they showed all through their early years. In the account of their death the hagiographical element is strengthened even more: whereas in the Tale Boris and Gleb shed tears and pray for mercy, in the Reading they accept death joyfully and prepare to meet it as the noble suffering for which they have been preordained since birth. The Reading, also in keeping with the requirements of the genre, contains an account of the saints’ posthumous miracles, the miraculous “discovery” of their relics, and the healing of the sick by their grave.

If we compare The Life of St Theodosius of the Caves, on the one hand, and the Tale, and particularly the Reading concerning Boris and Gleb, on the other, we can see different tendencies in them. Whereas in The Life of St Theodosius of the Caves realistic details broke through the hagiographical canons, in the Lives of Boris and Gleb the canon prevails and in some cases distorts the authenticity of the situations described and the characters. Nevertheless the Tale, more than the Reading, shows a lyrical quality which is most evident in the death scene soliloquies of Boris and particularly of Gleb who grieves for his father and brothers and fears his imminent death.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature