The Synodical for Ermak’s Cossacks

The Synodical did not only contain the “names of the slain,” i.e., it was more than a simple list of names. Cyprian included the Synodical in the Feast of Orthodoxy ritual according to which praises were sung in Lent for people revered by the Church and heretics and sinful people were anathematised. Short narrative passages and stories were allowed in the Feast of Orthodoxy ritual. There are many such historical insertions in the version of this work that was preserved in the Tobolsk Cathedral of St Sophia. There are also narrative passages in the Synodical for Ermak’s Cossacks. It is, in fact, a brief account of the Siberian campaign, with a list of the main battles and a description of Ermak’s death. Here we find clearly formulated an idea that was later preached extensively by official Siberian literature, namely, that the Cossacks came to Siberia with the “shield of the true faith”, and that they shed their blood for the triumph of Orthodoxy to bring Christianity to this pagan land.

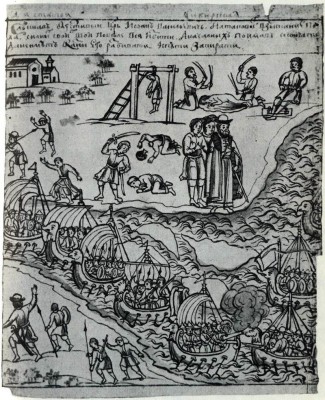

Ermak’s Journey Along the Siberian Rivers. Drawing for The History of Siberia by S. U. Remezov. The end of 17th century. Academy of Sciences Library, Leningrad

The Esipov Chronicle. This idea forms the basis of The Esipov Chronicle, named after its writer, Savva Esipov, who completed work on it in 1636. Savva Esipov was in charge of the Chancery of the Archbishop of Tobolsk (he had the post of archbishop’s secretary). Naturally Esipov, who was probably acting on direct instructions from the ecclesiastical authorities, had at his disposal both the Synodical and other documents in the library and archives of St Sophia which are unknown to us.

His chronide was conceived and written as a history of Siberia. After beginning with an account of the countryside, peoples, local rulers and princes, Esipov then concentrates on two figures, Kuchum and Ermak. He portrays Kuchum in the traditional mediaeval guise of the proud pagan ruler who tried the Lord’s patience sorely. Ermak is the instrument of the Lord, a “two-edged sword”. God chose a simple Cossak (“not of an illustrious line” the chronicle tells us), to put Kuchum to shame. Ermak as a person does not interest Esipov, only Ermak as the instrument of the Lord. The Siberian chronicler had not yet “discovered character”. The chronicle ends with an account of the founding of the Tobolsk archbishopric. This event testifies to the triumph of Orthodoxy in Siberia.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature