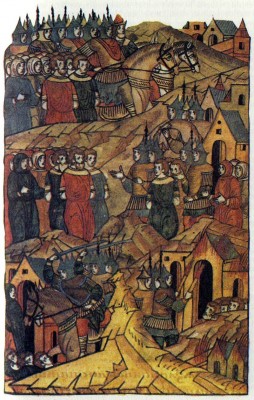

The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan

The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan is not a documentary account of the struggle of the people of Ryazan in 1237 against the enemy that invaded the principality. Among the participants in the battle many names are mentioned that are unknown in chronicle sources. Some of the princes who, according to the Tale, fought against Batu had already died by 1237 (for example, Vsevolod of Pronsk who died in 1208 and David of Murom who died in 1228) and Oleg the Red is said to have died in it (when in fact he was in captivity until 1252 and died in 1258). These deviations from historical fact suggest that the Tale was written some time after the actual event, when the real facts had undergone a certain epic generalisation in people’s minds. The epic generalisation of the work can also be seen in the fact that all the Ryazan princes who fought in the battle against Batu are joined together in a single gigantic host and called brothers in the Tale. At the same time we must not date the writing of the Tale too long after the event which it describes. It was probably written not later than the middle of the fourteenth century. This, Dmitry Likhachev writes, “is also suggested by the intensity of the sorrow at the events of Batu’s invasion, which has not yet been softened or diminished by time, and a number of characteristic details that could have been remembered only by the closest generations”.27

We are examining The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan together with thirteenth-century works dealing with the Mongol invasion because it reflects epic legends about Batu’s campaign against Ryazan, some of which may have been created shortly after 1237.

The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan gives the impression of being an independent work, although in the Old Russian manuscript tradition it is part of a compilation consisting of texts about an icon of St Nicholas. This icon was taken to the Ryazan lands from Korsun (Chersonesus),[1] the town in which, according to legend, Vladimir I was baptised and where many Russians lived before the Mongol invasion. The compilation consists of: 1) The Tale of St Nicholas of Zarazsk, the story of how the icon of St Nicholas was brought from Korsun to the principality of Ryazan by the “keeper” of the icon, Eustathius; 2) The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan; 3) The Encomium of the Princely House of Ryazan; and 4) the “family tree” of the “keepers” of the icon.

The first story is based on a subject very common in mediaeval literature, namely the transfer of sacred objects (a cross, an icon, relics, etc.) from one place to another. Here this traditional subject is closely connected with the historical situation immediately preceding Batu’s invasion.

The Tale of St Nicholas of Zarazsk begins with an indication of when the event took place—“In the year 6733 (1225). In the reign of the Grand Prince George of Vladimir … a wonderworking icon was brought…”28 St Nicholas appears to Eustathius several times in a dream and commands his “keeper” to take his icon from Korsun to Ryazan. Dmitry Likhachev gives the following answer to the question of why St Nicholas “drove” Eustathius from Korsun to Ryazan: “Eustathius was driven not by St Nicholas, of course, but by the Polovtsians who began to move after the battle on the Kalka, alarmed by the advance of the Mongol hordes, overran the Black Sea steppes and cut Korsun off from the Russian north. We should remember that Eustathius’ journey took place in the ‘third year after the battle on the Kalka’ and that St Nicholas ‘forbade’ Eustathius to cross the dangerous polovtsian steppes. It is also no accident that Ryazan was chosen as a safer place for the ‘patron’ of trade, St Nicholas. Ryazan’s links with the Northern Caucasus and the Black Sea coast can be traced back to early times.”29

After many misadventures Eustathius eventually arrives in the land of Ryazan. St Nicholas appears to the Ryazan Prince Theodore, son of Yuri (no prince of that name is mentioned in the chronicles), orders him to give his icon a solemn welcome and predicts that the prince, and his future wife and son will gain the “Kingdom of Heaven”. The story ends with an account of how St Nicholas’ prophesy comes true. In 1237 Theodore was killed “by the godless ruler Batu on the river at Voronezh”. Hearing of her husband’s death Theodore’s wife, Princess Eupraxia, kills herself and her young son Ivan by jumping “from her high palace”. After that the icon of St Nicholas became called the icon of St Nicholas of Zarazsk because the pious Princess Eupraxia zarazilas, “jumped to her death”, with her son, Prince Ivan. Thematically The Tale of St Nicholas of Zarazsk is closely connected with the following Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan, from which we learn how and why Prince Theodore was killed by Batu and what suffering Batu brought to the land of Ryazan.

The Tale begins in the manner of a chronicle: “In the year 6745 (1237) … the godless ruler Batu came to the land of Russia…” Then follows a passage similar to the chronicle account of the coming of Batu saying that Batu demanded a tithe of everything from the people of Ryazan and announcing the refusal of the Grand Prince of Vladimir, to go to the aid of Ryazan.

Grand Prince Yuri of Ryazan, not receiving aid from the Prince of Vladimir, consults with his fellow princes and decides to placate Batu with gifts. His son Theodore takes gifts from Ryazan to Batu. Batu accepts them and promises to spare the Ryazan principality. But then he “began to ask the princes of Ryazan for their daughters and sisters to share his bed”. One of the Ryazan noblemen out of envy told Batu that Theodore’s wife “is of noble birth and fairer in body than all others”. In reply to Batu’s demand to “taste the beauty” of his wife, the prince “dared to reply to the ruler: ‘It is not fitting for us, Christians, to bring our wives to you, impious ruler, for lechery. When you conquer us, then shall you possess our wives also.’ ” Infuriated by Theodore’s bold reply, Batu orders the prince and all those with him to be killed. The death of Eupraxia and her son is described in almost the same words as in The Tale of St Nicholas of Zarazsk.

This is the exposition of the Tale. Although at first glance this episode seems to be self-contained, it is closely connected with the main theme of the work, namely, that all attempts to mollify the enemy and come to terms with them are pointless and can lead only to total subjection. The only solution is to fight against the invaders, even if this struggle will not lead to victory. The exposition of the Tale is linked with the subsequent development of the subject by Yuri’s appeal to the princes and men of Ryazan, when the news of his son’s death reaches the city: “It were better for us to win eternal glory through death, than to be in the power of pagans.” This summons to fight the foe contains the main theme of all the episodes in the work, that death is better than shameful slavery. Yuri’s words remind one of Igor Svyatoslavich’s address to his men before they set off on their campaign in The Lay of I gov’s Host: “O brethren and warriors! Better be slain than taken captive!” This is not evidence of a direct link of the Tale with the Lay. More likely this coincidence is explained by the identical view of military honour, patriotism and civic fervour of the two works.

The men of Ryazan met Batu by the frontiers of the Ryazan land “and fell upon him, and began to fight him hard and bravely, and a cruel and terrible battle ensued. The Russians fought so bravely that even Batu was alarmed. But the enemy forces were so great that there were a thousand of them to each Ryazan man, and each two Ryazan men fought “against ten thousand”. The nomads marvelled at the “strength and courage” of the Russians and had difficulty in overcoming them. Listing the princes killed in the battle by name, the author of the Tale says that all the other “valiant and daring men of Ryazan” “perished likewise and drained the same cup of death to the dregs”.

Having destroyed Yuri’s army, Batu began to conquer the land of Ryazan. After a five-day siege his men took Ryazan. “And not a single living soul remained in the town: all died and drained the same cup of death to the dregs.” The silence that descended after the fierce battle and terrible slaughter (“There was no groaning and no lamenting there”) is eloquent testimony to the mercilessness of the enemy. The same idea is stressed by the words that there was no one to grieve the dead: no fathers and mothers to mourn their children, and no children to mourn the death of their parents, no brothers to mourn their brothers—all lay dead together.

Having sacked Ryazan, Batu advanced on Suzdal and Vladimir, “intending to capture the Russian land”. At this time “a certain nobleman by the name of Evpaty Kolovrat from Ryazan” was in Chernigov. Learning of the disaster, he galloped to Ryazan, but it was too late. Then he gathered together a band of “one thousand seven hundred men whom God had preserved outside the town”, hurried off “in pursuit of the godless ruler, and managed to catch him up in the land of Suzdal”. Evpaty’s men fought with such reckless bravery that the enemy “became like drunken or mad men” and “the Mongols thought the dead had come to life”.

Evpaty’s attack on Batu’s immense army with a small band of Ryazan men who had accidentally survived the earlier slaughter ended in defeat. But it was an heroic defeat, symbolising the military valour and selfless courage of the Russian warriors. The enemy managed to kill the “mighty giant” Evpaty only with the help of battering rams. Like a legendary knight, Evpaty felled a vast number of Batu’s best men, chopping some in two and cleaving others “to the saddle”. The men with him also fought like heroes of folk legends.

The style of the folk epos is felt not only in the figures of Evpaty and his men, but in the whole character of this episode. Batu’s men succeed in capturing a few Ryazan men “faint with wounds”. When asked by Batu who they are and who has sent them, the captives reply in traditional epic fashion: “We come from Prince Ingvar Ingorevich of Ryazan, to honour you, mighty ruler, and to accompany you with honour and to do you honour.” They ask Batu not to “take offence”: there are so many of you, they say, that we shall not have time “to fill the cup for such a great Mongol host”. The episode ends with the words that Batu “marvelled at their wise reply”.

Batu and his generals were forced to acknowledge the immense bravery and unprecedented courage of the Russian warriors. Gazing at the dead body of Evpaty, Batu’s princes and generals say that never before have they “seen such valiant and daring men” nor heard from their fathers of such courageous warriors who like “winged men do not know death and fight so hard and bravely, riding on their steeds, one to a thousand and two to ten thousand”. Looking at Evpaty’s body, Batu exclaims:

“If such a man served me, I would hold him right next to my heart.” The surviving warriors from Evpaty’s band are allowed to leave unharmed with the hero’s body. The attack on the foe by Evpaty’s men is revenge for the sacking of Ryazan and its dead.

After the Evpaty episode comes an account of the arrival in Ryazan from Chernigov of (according to the Tale) the only surviving Ryazan Prince Ingvar. At the sight of the terrible devastation of Ryazan and the death of all his kin Ingvar “shouted with compassion, like a trumpet summoning a host, like a sweet sounding organ”. His grief is so great that he falls to the ground “like a corpse”. Ingvar buries the remains of the dead and f mourns them. In its imagery and phraseology his lament is akin to folk laments. The author of the Tale makes extensive use in his work of folk epic legends about Batu’s sacking of Ryazan. The epic element is most noticeable in the story of Evpaty Kolovrat. Some specialists take the view that the Evpaty episode is in fact an epic song about Evpaty Kolovrat that has been inserted into the text.30 But th.e fate of Prince Theodore, his wife and son in the Tale are also organic parts of a single, complete narrative. And all these parts are firmly bound together by a single idea, that of the selfless courageous defence of the homeland against the enemy invasion, by the single thought that “it were better for us to win eternal glory through death, than to fall into pagan hands”. This central idea of the Tale makes it a story of the heroism and greatness of the human spirit.

After The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan comes The Encomium of the Princely House of Ryazan. “Those sovereigns … were of Christ-loving lineage, brother-loving, fair of face, bright-eyed, dread of countenance, immeasurably brave, light of heart, kind to their boyars, welcoming to guests, diligent to the church, quick to feast, ready for their sovereign’s amusements, skilled in warfare, and majestic before their brothers and envoys. They had a manly mind, dwelt in truth, and observed purity of soul and body without sin…” The Encomium stresses the human, spiritual and stately virtues portraying the ideal Russian prince, and the embodiment of this ideal are the Ryazan princes that have been killed. The Encomium stands out particularly for its literary mastery.

The Tale of Batu’s Capture of Ryazan is a masterpiece of Old Russian literature. The description of Batu’s march on Ryazan is of a narrative nature. The reader follows the development of the events with tense interest. He feels the tragedy of what is taking place and the heroic selflessness of the men of Ryazan. The Tale is full of a deep patriotism that could not fail to move Old Russian readers, and is also easily understood and shared by readers today. The artistic force of the Tale lies in the sincerity with which the author describes the heroism of the men of Ryazan, in the compassion with which he relates the disasters that befell the Ryazan land. The Tale shows a high degree of literary perfection. This can be seen, inter alia, in the fact that the author has managed to mould into a single heroic narrative episodes and motifs of oral epic origin and a high bookish culture. The Tale combines the folklore genres of the eulogy and the lament. This combination is characteristic of a number of the finest works of Old Russian literature: The Lay of Igor’s Host, The Encomium of Roman Mstislavich of Galich, and The Lay of the Ruin of the Russian Land.31

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature