The Works of Serapion of Vladimir

The Mongol invasion was also reflected in the oratorical genre, one of the main genres of Old Russian literature.

Serapion of Vladimir was a fine master of this genre in the thirteenth century. Very little is known about Serapion’s life. We know that up to 1274 he was Archimandrite of the Kiev Crypt Monastery and from 1274 to 1275 (the year of his death) Bishop of Vladimir. Serapion was appointed Bishop of Vladimir-Zalessky on the initiative of Metropolitan Cyril, a highly educated man for his day, who took part in the compilation of The Chronicle of Daniel of Galich and The Life of Alexander Nevsky. Both Serapion of Vladimir and Metropolitan Cyril were among the thirteenth- century figures who maintained cultural ties between South- Western Russia and the Russia of the north-east.

Five sermons by Serapion have come down to us, but from the description which the chronicler gives of Serapion when announcing his death under the year 1275 and from the works of Serapion himself it is obvious that he wrote far more sermons and homilies. The main theme of Serapion’s sermons are the disasters that have befallen the Russian land as a result of the Mongol invasion, which was Divine punishment to Russia for people’s sins. According to Serapion, only repentance and moral self-perfectionment can save the Russian land. Serapion’s vivid descriptions of the disasters that have befallen the Russian land and his depth of feeling for his people’s sufferings, which he himself shared, give his sermons great patriotic meaning.

Four of Serapion’s five surviving sermons were written by him in 1274-1275 in Vladimir.38 One of them, “On Divine Punishments and Battles”, was most likely written shortly after the destruction of Kiev by Batu in 1239-1240.

All Serapion’s sermons form, as it were, a single cycle in which the author describes with a heavy heart the terrible hardships of the enemy invasion and calls on people to cease their internal strife and cleanse themselves from their sins and shortcomings in the face of the terrible menace. In his Sermons he condemns the internecine warfare of the princes, greed, usury and violence.39

Both the general theme, central to all Serapion’s Sermons, namely, the merciless cruelty of the Mongols, and the individual questions with which he deals in them, are developed not in abstract, rhetorical discourses, but in realistic and convincing sketches. At the same time the author’s literary talent is evident throughout.

The dramatic solemnity of Serapion’s account of the disasters that have befallen the Russian people is achieved by alternating long series of parallel syntactical constructions with phrases in the form of a question: “…They ravaged our land, and captured our towns, destroyed our holy churches, killed our fathers and brothers, and violated our mothers and sisters”; “Is our land not captive? Are our towns not conquered? Have our fathers and brothers not fallen dead upon the ground? Have our women and children not been taken into captivity? Have not those who remained been enslaved with the bitter slavery of the infidels? For nigh on forty years bitter suffering and torment and tribute have lain heavily upon us, and hunger, and the plague has stricken our cattle. And we cannot eat our fill of our bread, and our bones are dried by our groaning and grief”; “Then God did send against us a pitiless people, a cruel people, a people who spare not the beauty of the young, nor the infirmity of the old, nor the infancy of children.”

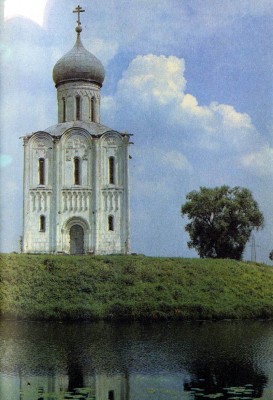

King David amid Beasts. Reliefs on the south fasade of the Church of the Intercession on the River Nerl

The general idea and sense of the pictures of violence wrought by the invaders and the hardships suffered by the people are similar in all the Sermons, but the concrete images and individual details vary throughout. No less vivid and lively are the passages in Serapion’s works where he dwells on moral questions and speaks of ignorance and superstition. Thus, for example, he condemns the cruel punishment of people suspected of sorcery and ridicules it most effectively. He says that if people believe that sorcerers can bring hunger or abundance, why burn them? If they really can do this, Serapion exclaims, “Pray to these sorcerers, and worship them, and make sacrifices to them—let them rule the community, and call down rain, and bring warmth, and command the earth to bear fruit!”

Serapion’s Sermons are a fine example of the noble art of oratory. They continue the traditions of such masters of this genre of Old Russian literature as Hilarion and Cyril of Turov. Unlike the works of these eleventh- and twelfth-century writers, Serapion of Vladimir’s Sermons convey first-hand impressions of the events of his age more strongly. They are written in simple, clear language.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature