Works of the Kulikovo Cycle. The Trans-Doniad

The victory of the Russians over the Mongols at Kulikovo Field not only made a great impression on contemporaries of this epoch-making event in Russian history, but also interested Russians for a long time afterwards. This is explained by the fact that the battle against Mamai was the subject of a number of literary works produced at different times, which were copied and revised by Old Russian writers throughout several centuries.

The works of the Kulikovo cycle vary in character and style. The poetic Trans-Doniad, the documental-historical original chronicle story, the intensely publicistic Extended Redaction of the chronicle story and, finally, The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai, full of military heroism, echoes of folklore and detail.9

The Trans-Doniad. The Trans-Doniad has already been mentioned above in connection with The Lay of Igor’s Host. Apart from its independent literary importance and the fact that this work is devoted to such an outstanding event in Russian history as the Battle of Kulikovo, The Trans-Doniad is important also as indisputable evidence of the age and authenticity of The Lay of Igor’s Host.

The Trans-Doniad was most probably written in the 1380s or early 1390s. It is a response to the Battle of Kulikovo and arose under the direct influence of the event itself.10

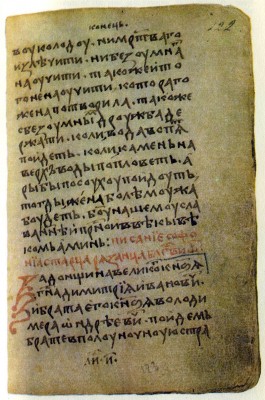

Six manuscripts of The Trans-Doniad have survived, the earliest of which (the Euphrosyne MS) dates back to the 1470s, and the latest to the end of the seventeenth century. The work is called The Trans-Doniad in the Euphrosyne MS. In the other manuscripts it is called The Lay of Grand Prince Dmitry, Son of Ivan, and His Brother, Prince Vladimir, Son of Andrew. The Euphrosyne MS is a condensed version of a non-extant original long text. In the remaining manuscripts the text is full of errors and distortions. Below we shall use the reconstructed text of The Trans-Doniad compiled on the basis of all manuscript copies of the work.11

The Trans-Doniad expresses the poetic attitude of its author to the events of the Battle of Kulikovo. The narrative (as in The Lay of Igor’s Host) moves from one place to another: from Moscow to Kulikovo Field, back to Moscow, to Novgorod and back to Kulikovo Field. The present intertwines with reminiscences of the past. The author himself describes his work as “a lament and eulogy to Grand Prince Dmitry, son of Ivan, and his brother, Prince Vladimir, son of Andrew”. The lament (zhalost) is for the fallen, and the eulogy (pokhvala) is for the courage and military valour of the Russians.

The whole text of The Trans-Doniad is related to The Lay of Igor’s Host: we find repetitions of whole passages from the Lay, identical descriptions and similar poetic devices. But the author of The Trans-Doniad makes creative use of the Lay. In taking it as the model for his work, Dmitry Likhachev writes, his purpose was not simply to imitate his model, but “to draw a deliberate comparison between the events of the past and present, the events portrayed in The Lay of Igor’s Host and those of his day. And both the former and the latter are symbolically contrasted in The Trans- Doniad”.12 This comparison made it clear that lack of unity in the actions of the princes (as in the Lay) led to defeat, while the uniting of all in the struggle against the foe was the pledge of victory. At the same time this comparison showed that a new age had arrived and that now it was the “pagan Tartars, the infidels” who were being defeated, not the Russians.

This comparison of the past with the present, of the events described in the Lay with those of 1380, runs right through the text. It is expressed vividly already in the introduction and is of profound significance. The author dates the beginning of the disasters that have befallen the Russian land to the ill-fated encounter on the Kayala and the Battle of the Kalka: Russia’s enemies “overcame the tribe of the Japhetites (i.e., the Russians) on the River Kayala. Since then the land of Russia has been joyless; from the Battle of the Kalka to the rout of Mamai it has been consumed with anguish and grief.” The victory over Mamai was a turning point in the fate of the Russian land: “Brothers and friends, sons of the land of Russia! Let us gather together, put word to word, gladden the land of Russia, and cast off sorrow to the Eastern lands.”

Describing Dmitry Donskoy setting off on his campaign, the author of The Trans-Doniad says that “the sun shone brightly for him in the East and showed him the way”. In The Lay of Igor’s Host the departure of Igor’s army is accompanied by an eclipse of the sun. (“Then Igor gazed up at the bright sun and he saw a shadow from it overcasting all his host.”) Describing the advance of Mamai’s forces to Kulikovo Field, the author of The Trans- Doniad presents a picture of natural phenomenon that bode ill: “And their destruction (the Tartars) was awaited by winged birds hovering in the clouds, the ravens cawed ceaselessly, and the jackdaws spoke in their tongue, the eagles screeched, the wolves howled menacingly and the foxes yelped, sensing bones.” In the Lay the same bad omens accompany the advance of the Russian host.

There are some poetical features of The Trans-Doniad that distinguish it from the Lay. The Trans-Doniad has far more imagery of a religious nature: “For the land of Russia and for the Christian faith”, “he stepped into his golden stirrup, mounted his swift steed, took his sword in his right hand, and prayed to God and to His Virgin Mother”, and so on. The author of The Lay of Igor’s Host made use of devices of folk poetry and adapted them creatively, fashioning his own original poetc images with material

from folklore. The author of The Trans-Doniad simplifies many of these images. His poetic devices deriving from folk poetry are closer to their prototypes. A number of original epithets in The Trans-Doniad are clearly of oral origin.

The Trans-Doniad has a mixed style. Poetic passages alternate with prose passages that remind one of official documents. It is highly likely that this mixture is due to the condition of the surviving manuscripts of the work: those passages where the style resembles officialese may be the result of later additions and not reflect the author’s original text of the work.

It is generally believed that The Trans-Doniad was written by Sophonius of Ryazan: this name is mentioned as the name of the author in the title of two manuscripts of the work. However, Sophonius of Ryazan is also called the author of The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai in a whole series of manuscripts of the main redaction of the Tale. The name of Sophonius of Ryazan is also mentioned in the text of The Trans-Doniad, and the nature of this reference suggests that we should probably regard Sophonius not as the author of The Trans-Doniad, but as the author of another poetic work on the Battle of Kulikovo which has not survived and which the author of The Trans-Doniad and the author of The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai used, independently of each other.13 We do not possess any other information about Sophonius of Ryazan apart from the mentions of his name in The Trans-Doniad and The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai.

The Trans-Doniad is an extremely interesting work of literature created in direct response to a major event in Russian history. It is also of interest because it reflects what was a progressive political idea for its time: namely, that Moscow should stand at the head of all the Russian lands and that the unity of the Russian princes under the power of the Grand Prince of Moscow was a sure pledge for freeing Russia from Mongol overlordship.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature