Historical Legends. The Cycle of Legends About John of Novgorod

Historical Legends. In terms of genre the historical legends that were widespread in the fourteenth and first half of the fifteenth century stand somewhere between the vita and the tale. Dealing with a single person and in a single text, they were read and intended as vitae. An example is The Life of Archbishop John of Novgorod. At the same time some episodes in Lives of saints had arisen independently and were inserted in these Lives later as historical legends, such as many of the episodes in the expanded redaction of The Life of St Barlaam of Khutyn. In historical legends real events are given a mystical interpretation. Below we shall examine the cycle of historical legends about Archbishop John of Novgorod as an example of this genre.

The Cycle of Legends About John of Novgorod. The Archbishop of Novgorod played an important role in the political and ideological life of the republic. The first Novgorodian Archbishop (before him the highest church dignitary there was the bishop) was John. John (Archbishop from 1165 to 1186) was extremely popular with the people of Novgorod both during his lifetime and after his death. Several legends belonging to different periods are connected with him. These are The Legend of the Battle of the Novgorodians with the Suzdalians, The Legend of John’s Journey to Jerusalem on a Devil’s Back, The Legend of the Finding of John’s Relics and The Legend of the Church of the Annunciation We shall examine the first two; which are the most interesting in terms of literary merit.38

The Legend of the Battle of the Novgorodians with the Suzdalians. The subject of this legend is the campaign against Novgorod in 1170 by the Suzdalians led by Mstislav (the son of Andrew Bogolyubsky), which ended in the victory of the Novgorodians. It is based on a folk legend and the short chronicle record of this event in The Novgorod First Chronicle. As a written work it appeared in the 1340s or 1350s.39

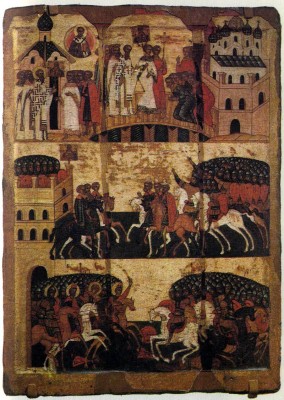

The Battle of the Novgorodians with the Suzdalians. Second half of 15th century. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Novgorod was besieged by the Suzdalians. Archbishop John prayed at night in his cell for the town to be saved. He heard a voice telling him to carry onto the town battlements the icon of Our Lady from the church in Ilyina Street (the Church of Our Saviour in Ilyina Street with frescoes painted by Theophanes the Greek in the late fourteenth century). During the storming of the town the icon, which had been placed on the town wall facing the besiegers, was hit by arrows. It turned to face the town and wept.40 Darkness descended upon the Suzdalians, and they killed one another.

The Legend gives a striking description of the church procession that carried the icon onto the battlements of the besieged town. The arrogance and complacency of the Suzdalians is stressed by the statement that they had already divided up the streets of Novgorod between themselves for looting and killing the townspeople. To stop the Virgin’s tears falling on the ground John collects them in his robe.

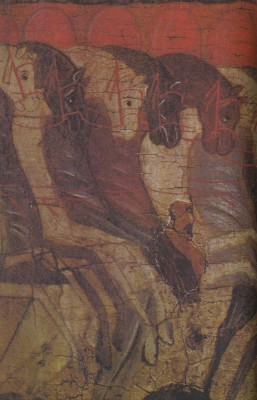

The Battle of the Novgorodians with the Suzdalians. Second half of 15th century. Detail of another icon

These striking images made a strong impression on all those who read or heard the Legend, as can be seen from the portrayal of this subject in Old Novgorodian painting. We know of two fifteenth-century icons and several later ones in which this subject is depicted. On the icons (which are known as the Sign from the Icon of the Virgin to specialists) the episodes are depicted in chronological order. The finest artistically is the icon of the middle or latter half of the fifteenth century now in the Novgorod Museum.41

The Legend of John of Novgorod’s Journey to Jerusalem on a Devil’s Back. The legend of John’s journey on a devil’s back appears to have arisen very early, but it is impossible to establish when the story based on this legend was written (it was probably not later than 1440, when John was made a locally revered saint).

One night when John is praying in his cell a devil decides to frighten him and distract him from his devotions: he creeps into the saintly man’s water-pot and begins splashing about in it.[1] John makes the sign of the cross over the water-pot and trapped the devil inside it. In return for his release the devil carries John to Jerusalem and back in one night on condition that John shall not tell anyone about the journey. But John accidentally lets out the secret, although he does not mention his own name. The devil gets his revenge on the saint: assuming the guise of a young maiden he walks out of the Archbishop’s cell for all to see, and when some high-ranking townspeople come to visit John, the devil bewitches them into thinking they can see some articles of female apparel in the Archbishop’s cell. The Novgorodians accuse their spiritual pastor of fornication and decide to drive him out of the town. John is put on a raft and the raft pushed off down the River Volkhov. But the raft, although unnavigated, floats upstream to the St George Monastery. Persuaded of John’s innocence and realising that their suspicions were the work of the devil, the Novgorodians walk along the bank after the raft, begging John to return to Novgorod.

The legend of how John trapped a devil with the sign of the cross and made him serve him originated in Old Russian folklore. This motif is widespread in the folklore of many countries.

The Legend reflects features of Novgorodian everyday life and is full of local colour. It stands out for its dynamic, exciting plot and realistic portrayal of events. The fact itself is miraculous, but it is conveyed with lively, realistic detail. This brings the story of John’s journey on a devil’s back close to the realm of fairy tale.

The description of the devil’s revenge is very reminiscent of the fairy tale in its humour and cunning.

The episode of a devil being trapped in a vessel is also found in the Old Russian Life of Abraham of Rostov (fifteenth century). There is an account of a devil’s revenge which is similar in a number of respects to the corresponding section of John’s journey on a devil’s back, in the Old Russian Tale of Bishop Basil of Murom (mid-sixteenth century). Both these monuments are secondary in relation to The Legend of John of Novgorod.

A characteristic feature of Novgorodian historical legends is their peculiar “authenticity”. They not only tell of concrete historical personages and events, but are confirmed by “material evidence”, e.g., the icon that was carried onto the town walls in 1170 and John’s water-pot.

The historical legends of old Novgorod have survived mostly in vitae and the Novgorodian chronicles. As Dmitry Likhachev remarks, the most popular and widespread legends that everyone knew “did not need to be recorded and written down in manuscript form… Only the need to use a legend in the liturgy or in the chronicle, to give it literary form, could save it from oblivion.”42 This gives us grounds for assuming that in oral tradition, and possibly in a written form no longer extant, there was a vast number of legends of which only a few have survived in the form of historical legends.

The literature of the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth century reflects the events and ideology of the period when the principalities of North-Eastern Russia were uniting around Moscow, the period of the formation of the Russian nation and the gradual emergence of the Russian centralised state.

As in the preceding periods the main literary genres were chronicle-writing and hagiography. The travel genre was revived. The genre of historical legends, that brought the hagiographical genre closer to the fictional narrative, became widespread. Historical tales and legends were created both in chronicle-writing and independently of it and are most widely represented by the works of the Kulikovo cycle.

During this period chronicle-writing developed intensively and the political and publicistic importance of chronicles grew. Chronicle-writing assumed an All-Russian character, and Moscow became its centre. The Moscow chronicles included much material from chronicles of all the Russian lands and also non-chronicle material, such as tales, legends, vitae and official documents. Chronicle-writing became a powerful ideological weapon in the political struggle to unify the Russian lands around Moscow and create a single centralised state.

The works of the Kulikovo cycle occupy a special place in the literary history of this period. These works are noteworthy not only because they reflect such an important event in Russian history, but also because of their literary significance. The Trans-Doniad revived the poetic traditions of the greatest work of Old Russian literature, The Lay of Igor’s Host, while The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai marked the beginning of a new type of historical narrative, the lengthy, non-chronicle story of an historical event, a story which combined hagiographical, military-heroic, rhetorical and publicistic elements together with an attempt to make the event depicted appear as exciting as possible.

Pre-Renaissance features of this period are felt most strongly in hagiography. Interest in man and his spiritual world led to a growth of the subjective element in literature, the desire to portray man’s psychological state. The expressive-emotional style emerged in hagiography.

Interest in the hero’s inner world did not yet lead to attempts to portray individual human character. The revealing of the hero’s psychological states and emotional experiences did not become a reflection of the individual in question, but remained an abstract expression of the qualities that the person was supposed to possess as the representative of a certain class, as the bearer of good or evil. This explains the oversimplified, one-sided descriptions of heroes and their behaviour. But at the same time writers did introduce elements of a concrete, personal nature in the portrayal of this or that generalised image.

The characteristic features of the literature of the fourteenth and first half of the fifteenth century were to find further development and even greater flowering in the second half of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century.

[1] An old copper water-pot said to have belonged to John is now in the NovgorodMuseum in the Cathedral of St Nicholas in the Dvorishche.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature