Historical Narrative

In the sixteenth century Russian chronicle-writing became centralised. Chronicles could be compiled in both the metropolitan and the grand prince chancelleries, but all records of current events were standardised. Consequently, if there was a change in the policy of the grand prince, these records were revised accordingly.

Two large All-Russian chronicles have survived from the sixteenth century—the Nikon and the Resurrection chronicles; on the basis of The Nikon Chronicle the multi-volumed sixteenth- century Illustrated Chronicle was compiled. Alongside All-Russian chronicle-writing local chronicle-writing continued in Pskov; individual chronicles were also compiled in Novgorod and the north of Russia, the Dvina lands and Kholmogory.

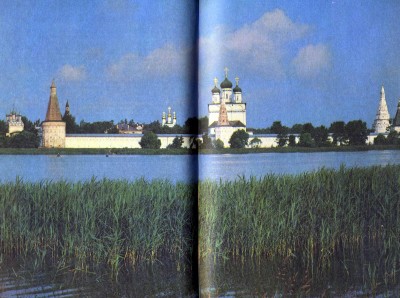

After the suppression of the heretical movements in 1504 a considerable role in the development of Russian literature was played by the victors, the “militant churchmen”, whose main citadel was the Volokolamsk Monastery founded by Joseph; after Joseph’s death his pupil, Daniel, became abbot of the Volokolamsk Monastery. In 1522 Daniel was appointed metropolitan, head of the RussianChurch. At the same period two very similar chronicles were compiled with the direct participation of Daniel: The Josaphat Chronicle, which covers the years from 1437 to 1519 (it is called Josaphat after Metropolitan Josaphat to whom it later belonged), and the chronicle that later became called The Nikon Chronicle by historians. The Nikon Chronicle was extremely large in size and complex in content; in its compilation use was made of an early fifteenth-century chronicle similar to The Trinity Chronicle, Tver and Novgorodian chronicles, a chronicle compilation transcribed in the Volokolamsk Monastery, and so on. But in the final section, which covers the history of the early sixteenth century, The Nikon Chronicle reproduced the official chronicle-writing of the grand prince.

A little later, in the 1530s (the period of Ivan IV’s infancy and “boyar rule”), a chronicle appeared which specialists now call The Resurrection Chronicle. It was compiled in the grand prince’s court and based on a Moscow grand prince’s compilation of the late fifteenth century.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, during the reforms of Ivan IV, the Council of the Hundred Chapters and the conquest of the Kazan Khanate, a special official Chronicle was compiled extolling the young ruler who had been crowned tsar a few years earlier. It bore the title of The Chronicle of the Beginning of the Reign of the Tsar and Grand Prince Ivan, Son of Basil This chronicle soon acquired a lengthy preceding section based on The Nikon Chronicle of the 1520s.

Thus we have the second redaction of The Nikon Chronicle, taken up to the 1550s.13

In the 1560s the last and most official redaction of The Nikon Chronicle with a large number of miniatures was compiled—The Illustrated Chronicle. This compilation consisted of nine volumes, three dealing with world history and based on the Bible, The Hellenic Chronicle and The Russian Chronograph, and six based on The Nikon Chronicle supplemented from The Resurrection Chronicle. Of particular interest is the fate of the last volume dealing with the reign of Ivan IV himself, but continued much further than The Chronicle of the Beginning of the Reign—up to 1567. There are two extant versions of this volume, one incomplete and not illuminated, which is called The Tsar’s Book The last volume of The Illustrated Chronicle shows traces of work by a redactor, who deleted the previous text and inserted in its place a new text in cursive script quite different in content. Many of these amendments attacked persons who suffered under Ivan IV. One of them (which we shall discuss later) describes events during the illness of Ivan the Terrible. The authorship of these amendments is a matter of dispute between historians: it could- have been the tsar or his secretary Ivan Viskovaty, but in any case they were official and reflected the policy of the period of the Oprichnina. Some of them were made in the main text of the new version of the last volume of The Illustrated Chronicle. The incompleteness of The Illustrated Chronicle which breaks off in 1567 and the cessation of official All-Russian chronicle-writing after this date were obviously connected with the drastic political changes in the years of the Oprichnina.14

A number of stories contained in the Russian chronicles of the sixteenth century are of literary, as well as historical value. These include the accounts of the end of Pskov’s independence, Basil Ill’s death in 1533 and Ivan IV’s illness in 1563.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature