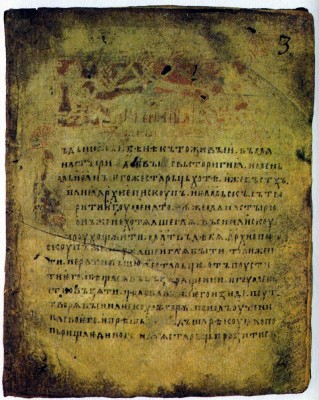

Paterica

Paterica, collections of short stories usually about monks famed for their piety or asceticism, were well known in Kievan Russia.

The Sinai Patericon, translated in Russia in the eleventh century, contains a story, for example, about a stylite[1] who was so self-abnegating that he even left alms for beggars on the steps of his abode and did not hand them over himself, saying that it was the Virgin, not he, who gave to the needy. There is also a story about a young nun who puts her eyes out when she learns that their beauty has aroused desire in a young man. A righteous monk is accused of committing adultery, but in reply to his prayer a twelve-day-old infant answers the question “Who is his father?” by pointing to his real father. One hot day in response to the prayers of a devout sea-captain rain pours down onto the deck, quenching the thirst of the suffering travellers. A lion meets a monk on a narrow mountain path and stands on its hind legs to let him pass, etc.

Whereas the righteous are accompanied by divine help, what awaits the sinners in patericon legends is terrible and immediate retribution, characteristically in this life, not in the next. The thief who defiles graves has his eyes put out by a corpse that comes to life; a ship will not move until a woman child-killer has been taken off in a boat, and the boat with the sinful woman is immediately swallowed up by the waves; a servant who is planning to kill and rob his mistress is rooted to the spot and stabs himself to death.

The paterica depict a fantastic world in which the forces of good and evil are constantly struggling for people’s souls, in which the righteous are not merely pious, but pious to the point of frenzy and exaltation, in which miracles sometimes happen in the most prosaic settings.

The subject matter of translated paterica influenced the work of Old Russian writers: in the Russian paterica and vitae we occasionally find similar episodes and descriptions borrowed from Byzantine patericon legends.17

Patericon legends were used by nineteenth-century Russian writers, such as Lev Tolstoy, Nikolai Leskov and Vsevolod Garshin.

[1] A stylite was the name given to a recluse who lived in a cell built on the top of a pillar (Greek “otύλos”) or in a small pillar-shaped cell.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature