Patristics

In Old Russian, as in any other mediaeval Christian literature, great authority was attached to patristics, the writings of Roman and Byzantine theologians of the third to eleventh centuries who were revered as “Church Fathers” (Greek patros and Latin pater mean “father”, hence the name given to their writings—patristics).

The writings of the Church Fathers substantiated and commented upon the basic precepts of the Christian religion, carried on polemics with heretics, and expounded principles of Christian morality or rules of monastic life in the form of instructions and exhortations.

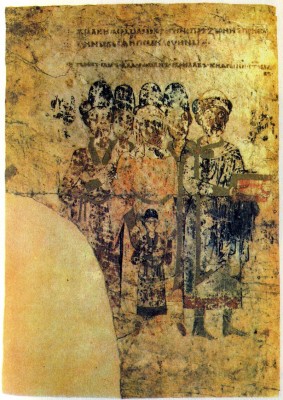

Prince Svyatoslav of Kiev with His Wife and Sons. Illumination from tin Svyatoslav Miscellany of 1073. History Museum, Moscow

In Old Russia the writings of St John Chrysostom (c. 350-407), the eminent Byzantine preacher, were widely read. In his discourses and sermons John exhorted believers to practise the Christian virtues, passionately denounced sins and occasionally condemned social injustice. In Bulgaria during the reign of King Simeon a collection of his works entitled The Stream of Gold was compiled, the oldest Russian copy of which belongs to the twelfth century; individual sermons of St John Chrysostom are included in Russian miscellanies of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries miscellanies were compiled in Russia with a fixed set of items. They were the Chrysostom and the Festal Sermons which also include a large number of the Byzantine theologian’s writings. In addition, passages from St John Chrysostom’s writings were widely used in the homilies compiled by unknown Russian scribes, but also frequently signed with his name.

The works of the following writers also enjoyed great authority in Old Russia: the Byzantine preacher St Gregory of Nazianzus (Gregory the Theologian) (329-390), St Basil the Great (c. 330-379), the author of polemical and dogmatic works and the Hexae’meron (a cycle of sermons on the Bible story of the Creation that enjoyed great popularity in the Middle Ages), St Ephraem of Syria (died 373), St Athanasius, the author of the Pareneses (a collection of exhortations for newly-converted Christians), St John Climacus (died 649), the author of the Ladder to Paradise (on the attainment of moral perfection), and St Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 295-373), who championed orthodox dogmas against the various heresies of the early Christian period. Patristic literature played an important role in forming the ethical ideals of the new religion and in strengthening the foundations of Christian dogma. At the same time the works of the Byzantine theologians, most of whom were brilliant rhetoricians who had mastered the finest traditions of classical rhetoric, helped to improve the oratorial skills of Russian religious writers.

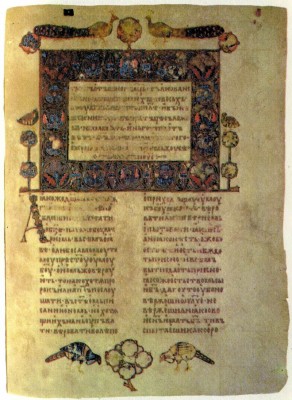

Kievan Russia was also familiar with miscellanies which, as well as the works of the Church Fathers, contained other writings of varied content. The oldest extant specimens of these are the two miscellanies of the 1070s. One of them, the Svyatoslav Miscellany of 1073, is a copy of a Bulgarian work compiled at the beginning of the tenth century for King Simeon of Bulgaria. The Miscellany was copied in Russia for Prince Izyaslav of Kiev, but the prince’s name was later erased and replaced by that of Svyatoslav, who seized the throne in 1073. The Miscellany is a folio of large dimensions executed with sumptuous artistry. The frontispiece (the left-hand side of the first sheet) bears a picture of Svyatoslav surrounded by his family. The items in the Miscellany include a handbook on rhetoric written by Georgios Choiroboskos entitled “Concerning Figures of Speech”, in which he explains the meaning of the various tropes (allegory, metaphor, hyperbole, etc.) illustrating them with examples taken, inter alia, from the Iliad and the Odyssey. Many copies were subsequently made of the Svyatoslav Miscellany. To date 27 copies of its Russian redaction made between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries have come to light.11

The other work, the Miscellany of 1076, is simpler and smaller and was compiled, as the manuscript tells us, “in the year 6584 (1076) … in the reign of Svyatoslav, Prince of the Russian land.” Among the works in this Miscellany is an encomium on the reading of books and also a collection of sayings by Patriarch Gennadius of Constantinople (died 471).12

Collections of aphorisms appeared in Russia at a later period also. They included the very popular miscellanies The Wisdom of Menander the Wise, the sayings of Hesychius and Barnabas, and particularly Melissa (The Bee), a collection of aphorisms by ancient philosophers, quotations from the Bible and writings of the Church Fathers. A definitive study of the miscellanies of sayings and aphorisms has been made by Mikhail Speransky.13

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature