The History of the Grand Prince of Moscow

This work was The History of the Grand Prince of Moscow written by Kurbsky in 1573, when Poland was without a king, with the direct political aim of preventing the election of Ivan IV to the Polish throne.37

Kurbsky composes his narrative in the form of an answer to a question put by “many learned men”: how is it that the Prince of Moscow, once “good and deliberate”, has fallen into such villainy? In order to explain this, Kurbsky tells of the emergence of “evil habits” in Ivan’s ancestors: the forcing of Basil Ill’s first wife to take the veil and Basil’s “unlawful” marriage to Yelena, Ivan IV’s mother, the imprisonment of the “holy man” the birth “of the present Ivan in unlawfulness” and “voluptuousness” and his “nefarious deeds” in his youth. Having thus disclosed the original “sin” that gave rise to subsequent “sin”, Kurbsky goes on to speak of the “two learned men” who succeeded in turning to piety and military valour “the young tsar, brought up in evil passions and wilfulness without a father, who was most savage and had already tasted all manner of blood”. These two men are the Presbyter Sylvester of Novgorod, who began to instruct the young tsar during the “unrest” in 1547 and the “noble youth” Alexei Adashev; it was they who turned the tsar away from the companions of his revelries, “parasites and idlers”, and brought him into the company of “men of good sense and perfection”, the Select Council. The natural consequences of the beneficial influence of the Select Council, according to the History, were Ivan IV’s military successes, first and foremost, the conquest of Kazan, which is described in detail by Kurbsky as an eyewitness and participant in the war.

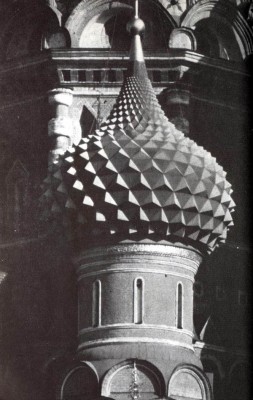

Cathedral of Basil the Blessed (the Intercession on the Moat) in Moscow. 1555-1560. Erected to commemorate the victory over the Khanate of Kazan

This was only the first half of the reign of the “Grand Prince of Moscow”. After the “glorious victory” at Kazan and the “burning ailment” that afflicted the tsar in 1553, a sudden change took place in him. This change was assisted by a monk who was one of the Josephites (Joseph of Volokolamsk’s followers whom Kurbsky accused of killing Vassian Patrikeyev), the former Bishop Vassian Toporkov, who advised the tsar not to have any counsellor wiser than himself if he wished to be an autocrat. Filled “with such death-dealing poison from the Orthodox bishop”, Ivan IV began to surround himself with “scribes” from the “common people” and persecute the “grandees”. He did not follow their good advice to continue the war against the Moslems and ignored their plans for the cautious and peaceful subjection of the land of Livonia.

The advice of Vassian Toporkov and the influence of “contemptible counsellors” led the tsar to cast aside and disgrace Sylvester and Adashev and persecute his own, formerly “most beloved” supporters. At this point Kurbsky ends his story about the Grand Prince of Moscow and turns to the second part of his pamphlet, a list of the “boyar and service gentry families” and “holy martyrs” destroyed by Ivan.

Such was the content of The History of the Grand Prince of Moscow, a work which Kurbsky sought to compose as a stylistically austere and elegant narrative, intended for readers well-versed in grammar, rhetoric, dialectics and philosophy. Nevertheless the author was unable to maintain this stylistic unity throughout and on at least two occasions had recourse to the device that he himself had so severely censured, namely, the portrayal of everyday scenes and the use of colloquial speech. Condemning the Lithuanian nobility for not being sufficiently militant in the early years of the Livonian war, Kurbsky describes how the “rulers” of the Lithuanian land, having partaken of “all manner of rich wines”, loll “on their thick feather-beds, then, after sleeping almost until noon, rise with bandaged heads heavy from drinking, barely alive and seek to regain their wits”. Without noticing it himself, he describes “beds”, which he had criticised Ivan for mentioning earlier. Kurbsky commits the same “sin” again when, clearly in response to Ivan’s description of his childhood, he gives his own version of the same events. He argues that the “great proud pany, in their language (Russian) the boyars”, who brought Ivan up, did not offend him, but, quite the reverse, pandered “to his every whim and passion”. And he tells how already in childhood Ivan began “to shed the blood of defenceless (animals), hurling them down from lofty places, or in their language from porches or from the upper storeys of houses…” Kurbsky does his utmost to avoid the prosaic detail of “foolish women”: he turns dogs or cats into abstract “defenceless creatures”, and porches into “lofty places”, but nevertheless he could not resist one lively detail—the description of the early cruelty of the orphaned prince who, later as tsar and writer, depicted his orphaned childhood so movingly.

Thus, the two major publicists of the sixteenth century eventually introduced observations from real life into their narrative.

Created in hard and unfavourable conditions the literature of the sixteenth century nevertheless represents an important stage in the history of Old Russian literature as a whole. The Renaissance elements found in works of the late fifteenth century could not develop in the age of Ivan the Terrible, when all subjects, from the most high to the most low, were regarded as the sovereign’s “slaves” without any rights. But in spite of the numerous obstacles new phenomena can be detected in sixteenth-century literature. In this literature, particularly the publicistic works of this period, the personality of the author is clearly felt. Almost all the writers of the sixteenth century are striking individuals, known to us by name and most unlike one another, such as Joseph of Volokolamsk and Vassian Patrikeyev, Daniel and Maxim the Greek, Ermolai-Erasmus and Peresvetov, Kurbsky and Ivan the Terrible.

For all the great differences between them, the publicists of the sixteenth century share one common feature characteristic of the European Renaissance, faith in human intellect, in the possibility of building society and the state on certain rational foundations. Many of them also took a secular view of the purpose of the state as an institution that served the common good (Ermolai-Erasmus and Peresvetov). Even Ivan the Terrible, who in practice tended towards the most unbridled use of force, in theory considered himself obliged to discuss measures without which “all realms would be racked by discord and internecine strife”.

In spite of the suppression of the Reformationist, humanist movements and the disappearance of “useless tales” (fictional, narrative), the literature of the sixteenth century reveals new features not characteristic of mediaeval literature. These new features were developed in the literature of the following century.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature