The History of the Jewish War by Josephus Flavius

This exceptionally popular work in European mediaeval literature was translated in Russia not later than the beginning of the twelfth century. The History was written between 75-79 A.D. by Josephus, the son of Mattathias, who took part in the rebellion in Judaea against Rome, and later went over to the side of the Romans and was granted the right to assume the name of Flavius, the family name of Emperor Vespasian.

The History consists of seven books. The first two contain a history of Judaea from 175 B.C. to 66 A.D., the period of the rebellion against Roman dominion, the next four describe the crushing of the rebellion by Vespasian, and later by his son Titus, and the siege, capture and destruction of Jerusalem; the final, seventh, book tells of the triumphal return of Vespasian and Titus to Rome.

Flavius’ History is by no means a dry historical account, but rather a literary, publicistic work. The author is tendentious. He does not hide his admiration for the mighty Roman emperors and his displeasure with his political opponents, the ordinary people of Judaea. Yet nor can he conceal his admiration for the courage of the rebels and his compassion for the sufferings that were their lot. The publicistic spirit of the work can be seen, in particular, in the speeches of Vespasian, Titus and Josephus himself (the author refers to himself in the third person). The main purpose of these speeches, which are constructed in full accordance with the rules of classical oratory, is to discredit the intentions of the rebels and extol the nobility and valour of the Romans. The stylistic art of Josephus Flavius is seen not only in the monologues and dialogues, but also in the descriptions, whether they are of the countryside of Judaea or its towns, battles or the terrible scenes of starvation in besieged Jerusalem; the rhythmic style, the vivid similes and metaphors, the apt epithets, and the concern for euphony (which is clearly evident in the original)—all this shows that the author attached great importance to the literary aspect of his work.

The Old Russian translator succeeded in preserving the literary merits of the original, its rich vocabulary, emotional speeches and lively descriptions. The translation also preserved the rhythmic segmentation of the sentences and parallelism of the syntactical constructions in the original. What is more, the translator independently expands the descriptions and makes them more concrete, replaces the indirect speech of the original by direct speech, adds new similes, metaphors and figures of speech that are traditional for Russian original works.25 Thus, the translation of the History testifies to the skill of Old Russian writers in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The History was extremely popular. And not only because it described one of the most important events in world history. Full of military episodes, it was of great interest to Russian readers who had many times experienced the trials of war and hostile invasion. No wonder the chronicle writers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries made use of favourite images or turns of phrase from the battle scenes of the History.

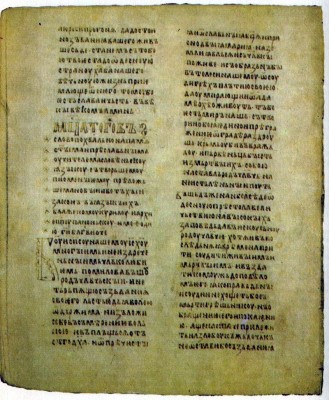

More than thirty manuscripts of the Old Russian translation of the History have survived. The oldest of these are to be found in the Archive and Vilna chronographs (late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) which date back to a chronographical collection of the mid-thirteenth century.26

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature