The Life of St Michael of Klopsk

Unlike the record of Innocentius, the Novgorodian Life of St Michael of Klopsk was not an account by an eyewitness, but a story based on oral legends about the life and miracles of this Novgorodian saint and yurodiviy (fool-in-Christ) who supported the princes of Moscow. But this vita too is not similar to the traditional Lives of saints: it is far closer to the folk tale-cum-novella.

The Life opens in an unusual way for a hagiographical work. It begins not with the usual account of the birth and upbringing of the saint, but with a description of the mysterious appearance of an unnamed person in the Klopsk Monastery near Novgorod. What we have here is a “closed” plot, as it were, the denouement of which is not known to the reader and arouses his curiosity.

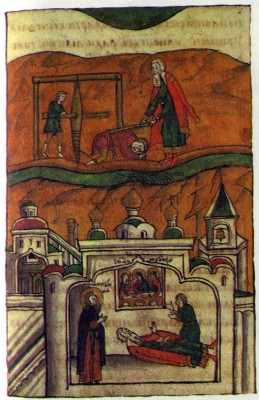

Illumination from The Life of St Michael of Klopsk in a 17th-century manuscript copy. Institute of Russian Literature, Leningrad

At nightfall on St John’s Day the priest Ignatius returns to his cell to find it unlocked. Inside is “an old man sitting on a chair with a candle burning in front of him”. The startled priest fetches Abbot Theodosius; this time the cell is locked. The abbot looks through the window and greets the stranger with a prayer; the stranger repeats the prayer. This happens three times. “Who are you? Man or demon? What is your name?” the abbot then asks him. “Man or demon? What is your name?” the stranger repeats. The abbot asks again: “Man or demon?” The stranger repeats his words again; this happens a third time also. Then the abbot has them tear down part of the roof of the lobby and begins to burn incense; the old man shields himself from the smoke of the censer, but crosses himself. This reassures the abbot, and the stranger is admitted to the monastery. The secret of his origin is not discovered until later, when Prince Constantine, son of Dmitry, visits the monastery and tells the monks that the stranger is a person of rank, related to the prince.17

Michael of Klopsk was a fool-in-Christ and this explains the eccentric nature of the stories about him to a large extent. This feature of the Life links it with secular literature of the kind that we shall be discussing later, for example, the legends about Solomon and Kitovras, in which, like Michael, the “wondrous beast” Kitovras can “see through” the present and future of people he talks to and conceals a profound wisdom behind his “foolishness”. The unusual structure of The Life of St Michael was noted by readers and subsequent redactors of the Life. In the sixteenth century when the Life was included in the large compilation of religious literature called The Great Menology (Church calendar readings), it was revised. The redactors tried to get rid of the unusual “closed” plot, in which the narrative began in the middle, as it were (with the arrival of the unknown old man in the monastery). They arranged the text in the traditional order for a hagiographical work and omitted the mysteries. True, the redactors apologised for the fact that they did not know “whence this wondrous teacher came from” and who his parents were, but immediately explained that he was no stranger, but “the wondrous Michael” who had decided to give up worldly things and find a fitting place for meditation. The unusual dialogue with which the first redaction of the vita began, when Michael repeats the abbot’s words, was also omitted. The redactor simply stated that Michael repeated what he heard from the abbot. Other scenes were altered in the same way. Instead of being shown, portrayed dramatically, the events were merely described.

Thus, the official hagiographers of the next century did not recognise the type of vita-cum-tale to which The Life of St Michael belonged. But this type did have its supporters, a fact that can be seen from the existence of other vitae that centred round an unusual hero whose wisdom is revealed in an unexpected way to those around him and to the reader. An example is The Life of SS Peter and Febronia of Murom, which has come down to us in a sixteenth-century redaction, but probably dates back to the fifteenth century.18

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature