The Main Ideological Phenomena of the Sixteenth Century

The sixteenth century was the period of the final formation and establishment of the Russian centralised state. During this period Russian architecture and painting continued to develop and book printing began. At the same time the sixteenth century witnessed the strict centralisation of culture and literature—the various chronicle compilations were replaced by the single national chronicle of the grand prince (later the tsar), and a single compendium of religious and some secular literature was set up known as The Great Menology, tomes in which the reading material was arranged according to months. The heretical movement that had been put down at the beginning of the sixteenth century re-emerged in the middle of the century after the large-scale popular revolts of the 1540s. And again heresy was cruelly repressed. One sixteenth- century heretic, a nobleman by the name of Matfei Bashkin, concluded boldly from the New Testament behest to love your neighbour that no one had the right to own “Christ’s servants” and freed all his serfs. Another heretic, a serf called Theodosius Kosoy, went even further by declaring that all people were equal irrespective of nationality and creed: “All people are equal before God, both Tartars, and Germans, and all other peoples.” Theodosius Kosoy fled from prison to Lithuanian (West) Russia where he continued to preach his beliefs, together with the boldest of the Polish-Lithuanian and West-European Protestants.

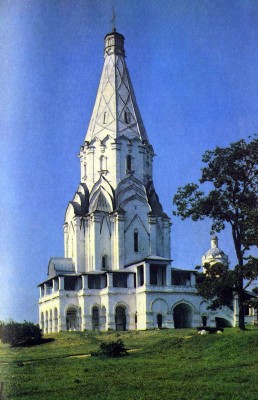

Church of the Ascension in the palace village of Kolomenskoye (now within the city limits of Moscow). 1536

Official ideology opposed the anti-feudal movements. The formation of this ideology can be traced from the early decades of the sixteenth century. Almost simultaneously, in the early 1520s, two most important ideological works appeared: The Epistle on the Monomachos Crown by Spiridon-Savva and The Epistle Against the Astrologers by the Pskovian monk Philotheus.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature