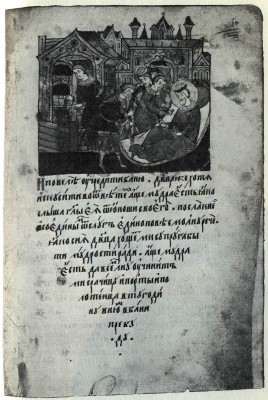

The Tale of Peter and Febronia

The hagiographical Tale of Peter and Febronia has come down to us in the work of the sixteenth-century writer and publicist Ermolai-Erasmus.10 There is scant information about this writer’s life. He came to Moscow from Pskov in the middle of the sixteenth century and became an archpriest in the court cathedral in Moscow, by the early 1560s took monastic vows (under the name of Erasmus) and possibly left the capital. His most important publicistic work was a treatise, in which he expresses the idea that peasants are the foundation of \ society: “First of all, the peasants are essential: from their labours comes bread, and from them most good things… and the whole country from the tsar down to the common folk is fed.” Believing the social inequality by which the peasant feeds his masters to be an inevitable phenomenon, Ermolai nevertheless suggests that the peasant’s payments and taxes should be strictly defined and that he should be protected from oppression by state land surveyors and tax collectors. Such measures, in his opinion, would reduce “all manner of rebellion”.11

As well as publicistic works Ermolai-Erasmus also wrote hagiographical ones, The Tale of Bishop Basil of Ryazan (later included in The Life of Prince Constantine of Murom) and The Tale of Peter and Febronia, which appear to have been based on a fifteenth-century vita.

The existence of a story of Peter and Febronia compiled before the end of the fifteenth century can be deduced from the fact that there is a fifteenth-century church service dedicated to Prince Peter of Murom who killed a dragon and to his wise wife Febronia, with whom Peter was buried in the same coffin. Evidently the basic subject of the tale dates back earlier than Ermolai-Erasmus.

The plot is as follows. Prince Paul’s wife is visited by a dragon in the guise of her husband. Paul’s brother, Peter, fights the dragon and kills it; but Peter is stricken down by the dragon’s blood that spurts onto him and his body is covered with sores.

Peter is cured by a wise peasant girl called Febronia; as a reward she asks the prince to make her his wife.

The subject-matter of the tale is reminiscent of many works in Russian and world folklore; it is also reflected in mediaeval written sources. In the famous West European (Celtic, Romance) legend of Tristan and Isolde the story also begins with the hero (Tristan) killing the dragon; he is cured by the heroine (Isolde).

However, the similarity between the subject matter of The Tale of Peter and Febronia and that of Tristan and Isolde stresses even more the difference in the respective treatment of the characters. Unlike the legend of Tristan and Isolde The Tale of Peter and Febronia is a story not about love, not about the all-consuming passion of the main characters, but about faithful conjugal life, and the main motif in the tale is the heroine’s quick-wittedness, her ability to outwit her adversaries, a feature which makes her akin to Olga in The Tale of Bygone Years.

Febronia appears in the tale after the sick Peter has sent messengers all over the land of Ryazan in search of physicians to heal him. During this search one of his servants comes to the village of Laskovo (meaning “tender”), which still exists to this day, and sees a girl at her loom; in front of her a hare is frisking about. In reply to the youth’s question as to the whereabouts of the other members of the household, she replies that her parents have gone “to weep to their credit”, and her brother “to look death in the eye through his legs”. The youth cannot make head or tail of these words, but the girl explains to him that her parents have gone to weep for the dead; when they die, people will weep for them too, so they are weeping to their credit; her brother is a wild-honey farmer who gets honey from trees and looks down through his legs so as not to fall to his death. Having ascertained that Febronia (the girl’s name) is very wise, the youth begs her to cure his prince. Febronia agrees on condition that Peter makes her his wife.

How are we to understand this condition? The reader who regarded the tale solely as a hagiographical work and Febronia, first and foremost, as a saint, could see this as a manifestation of her wisdom—she knew in advance that Peter was ordained to be her husband. But people brought up on folk tales, where such a condition is often met, could regard this motif in a different way, on a purely prosaic level. Living in her village of Laskovo. Febronia was unlikely to have even seen Peter before she was asked to cure him. The reader would naturally conclude that she was drawn to Prince Peter not by love (in the legend of Tristan and Isolde there is a reference to a love potion) but simply by the desire not to let her good luck slip through her fingers.

Febronia shows the same quick-wittedness and ability to outwit in her dealings with Peter. At first the prince puts her to the test: A he sends her a piece of flax and asks her to weave him a robe from it. But Febronia counters this impossible demand with one of her own[1]; she agrees to do as Peter asks on condition that the prince makes her a loom out of a splinter of wood. Peter cannot, of course, so he withdraws his request. After he has been healed Peter tries to break his promise to marry the peasant girl. But Febronia had prudently rubbed all his sores with ointment except one, and as a result of Peter’s treachery from “that sore many other sores began to appear on his body”; in order to be completely healed Peter has to keep his promise.

Peter marries Febronia, but the noblemen of the land of Murom do not want a princess who was a peasant girl. She agrees to leave Murom on condition that she is allowed to take what she wants with her. The noblemen agree and the princess wants “only my husband, Prince Peter”.

Peter and Febronia leave Murom together on a boat with other passengers. Among them is a certain married man who, egged on t by an evil spirit, looks lustfully at the saintly woman. Febronia advises him to scoop up and drink some water first from one side of the boat, then from the other. “Is that water the same or sweeter than the other?” she asks him. He replies that the water is the same. “And woman’s essence is the same also. So why leave your own wife and covet another man’s?” Febronia asked.

How are we to understand these scenes? Like the story of Peter’s marriage to Febronia, they too can be regarded in different ways: both as an indication of the heroine’s wisdom and as proof of her cunning. Febronia foresees that the stupid noblemen will not know what she is going to ask them for. In the same way her answer to the importunate fellow-traveller on the boat is witty and edifying, rather than openly didactic; one of the heroines of Boccacio’s Decameron (Day I, story 5) replies to the importunate advances of the French King in similar fashion.

The exile of Peter and Febronia does not last for long: the rebellious noblemen begin to quarrel and fight among themselves and prove incapable of retaining power, so Peter and Febronia are again summoned back to Murom.

The final scene is deeply poetic. As old age approaches the j hero and heroine take monastic vows and wish to die together. Peter is the first to feel the approach of death and calls Febronia to “depart” together. Febronia is embroidering a special cloth for the chalice. She embroiders the saint’s head only, then sticks her needle into the cloth, winds the embroidery thread round it, and dies together with her husband.

After the death of Peter and Febronia they are buried apart, but are miraculously reunited in the same coffin.

The Tale of Peter and Febronia was closely connected with folklore and also related to the “itinerant subjects” of world literature. With regard to Russian folk tales it is closest to The Seven-Year-Old Girl and The Shorn Maid which are also about the marriage of a person of noble birth to a peasant girl who proves her wisdom by solving difficult tasks; here too is the motif of exiling the heroine who takes her dearest possession—her husband. But in Russian tales (which have survived only in manuscripts of the modern age) we do not find the theme of the illness and healing of the high-born husband. It is obvious, however, that this motif was also present in the folklore subject used by Ermolai-Erasmus. In one of the stories of The Decameron (Day III, story 9) the heroine receives a courtier as a husband in return for healing the King of France, The unequal marriage brings her grief and banishment, but, as in the Russian tale, the heroine’s wisdom helps her to triumph. The same subject is also used by Shakespeare in his comedy All’s Well That Ends Well The combination of the themes of the unequal marriage and the healing of the hero by the heroine was obviously also known in Russian folklore of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The end of the tale of Peter and Febronia is also linked with folklore motifs and again reminds us of Tristan and Isolde, where the love of the twro main characters is stronger than death (a rose bush grows out of Tristan’s grave linking it with the grave of Isolde).

The untraditional nature of the hagiographical Tale of Peter and Febronia evidently made it unsuitable for the hagiographical canons of the sixteenth century. Although created at the same time as the final version of The Great Menology (the Assumption and Tsar’s menologies), it was not included in them. The folklore elements in the tale, its brevity, and lack of conventional features made it unsuitable for the hagiographical school of Metropolitan Macarius. But it is precisely these features that make The Tale of Peter and Febronia one of the finest works of Old Russian literature.

[1] This countering of something absurd with something equally absurd is characteristic of mediaeval literature. For example, Akir in The Tale of Akir the Wise does precisely the same.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature