The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky

Alexander (born circa 1220, died in 1263) was Prince of Novgorod from 1236 to 1263 and Grand Prince of Vladimir from 1252 to 1263. Both during his reign in Novgorod and as grand prince he led Russia’s struggle against the German and Swedish invaders.

In 1240 Swedish knights invaded the north-west of Russia. They sailed up the river Neva, stopping somewhere near the mouth of its tributary the Izhora (some say at the point where the settlement of Ust-Izhora now stands outside Leningrad, others at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Leningrad itself). With a small force of men Alexander attacked the enemy on June 15, 1240 and won a splendid victory over a large force. Hence his nickname, Alexander of the Neva (Nevsky). In 1241-1242 Alexander led the struggle against the Teutonic Knights who had captured the lands of Pskov and Novgorod. On April 5, 1242 on the ice of LakeChudskoye (Peipus) a decisive battle was fought that ended with the total defeat of the invaders, the famous Battle on the Ice.

Realising that it was futile at that time to launch an attack on the Golden Horde, Alexander maintained peaceful relations with the khan of the Golden Horde and pursued a policy of uniting the lands of North-East and North-West Russia and strengthening the authority of the grand prince. He travelled to the Horde several times and succeeded in releasing Russia from the obligation of providing troops for the Mongol khans. Alexander relied extensively on the assistance of the common people in his defence of Russian lands against external foes, which did not prevent him, however, from cruelly suppressing anti-feudal revolts by the masses (e.g., the uprising in Novgorod in 1259).

The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky is devoted to Alexander as the wise statesman and great military leader. The work was written in the Monastery of the Nativity in Vladimir, where Prince Alexander was buried (he died on his way back from a journey to the Horde).[1] In composition, manner of describing the battles, individual stylistic devices and certain phraseologisms The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky is similar to The Chronicle of Daniel of Galich. According to Dmitry Likhachev’s convincing argument, this is explained by the fact that Metropolitan Cyril played a part in the writing of both works. “There can be no doubt,” he writes, that Cyril was associated with the compiling of the biography of Alexander. He could have been the author, but more likely he commissioned the Life from a Galich writer living in the north.”40 That Cyril had something to do with the compiling of The Chronicle of Daniel of Galich is well argued by Lev Cherepnin.41 The Metropolitan died in 1280, therefore, The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky must have been compiled between 1263 and 1280.

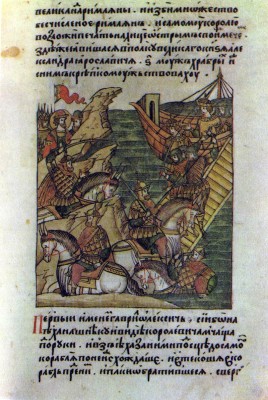

The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky. The Battle on the Neva and the Defeat of the Swedes in 1240. Illumination from The Illustrated Chronicle. 16th century. State Public Library, Leningrad

As well as being similar the Tale and the Chronicle also differ in terms of genre. The biography of Alexander Nevsky is a work of the hagiographical genre.42 This is reflected in many characteristic features of the work. First of all, in keeping with the canons of the genre, the author speaks of himself in the foreword, with exaggerated humility, using stock phrases: “I, a wretched, much-sinning man of little understanding, dare to write the Life of the saintly Prince Alexander…”43 Secondly, in keeping with hagiographical custom he begins his narrative by announcing the birth of Alexander and his parentage: “He was born of a merciful, loving and, furthermore, meek father, Grand Prince Yaroslav, and of his mother Theodosia.” Thirdly, the story of the miracle that happened after Alexander’s death is of a clearly hagiographical nature. Finally, the actual text contains constant digressions of an ecclesiastical and rhetorical nature and the prince’s prayers.

The story about Alexander Nevsky was intended to show that in spite of the conquest of the Russian principalities by the Mongols, there were still princes in Russia whose courage and wisdom could resist the enemies of the Russian land, and whose military prowess could inspire fear and respect in neighbouring peoples. Even Batu acknowledges Alexander’s greatness. He summons Alexander to the Horde: “Alexander, know you not that god has subjected many peoples to me? Why do you alone refuse to submit to me? If you wish to keep your land come quickly to me and you will see the glory of my kingdom.” When he meets Alexander, Batu says to his nobles: “It is true what I have been told that there is no prince the like of him.”

The author of the Tale, as he tells us at the very beginning of his story, knew the prince and witnessed his acts as a statesman and military feats: “I myself was a witness of his age of maturity.” Hagiographers often tell us in their works where they obtained information about the life of their hero. The author usually says that he found out about the saint from contemporary accounts, extant records, an earlier Life, or as his contemporary or pupil. It is rare for the author to say that he knew the saint himself; the wording of the Tale: “I myself was a witness…” is not found in any other Life. Therefore we have every reason to regard this phrase as documentary proof of the fact that the author was a contemporary of Alexander’s and personally acquainted with him.

Both the real figure of the prince, who is close to the author, and the tasks which the author sets himself give this hagiographical work a special military flavour. One can sense the narrator’s liking for Alexander and admiration of his military and political activity. This lends a special sincerity and lyricism to the Tale.44

The descriptions of Alexander in the Tale are on various levels. His “Christian virtues” are stressed in keeping with hagiographical canons. The author says that the Prophet Isaiah had in mind such princes as Alexander Nevsky when he said: “He loved priests and monks and beggars, revered the Metropolitan and the bishops and heeded them like Christ Himself.”

At the same time Alexander is of majestic and comely appearance, a brave and invincible military leader: “He was comely as no other, and his voice was like a trumpet among the people.” He is invincible. In his military operations Alexander is swift, dedicated and merciless. On hearing that the Swedish army has reached the Neva, Alexander “flared up in anger” and sped off “with a small bodyguard” against the enemy. He was in such a hurry that he could not “send news to his father”, and the Novgorodians did not have time to rally to his aid. Alexander’s impetuosity and military daring are characteristic of all the episodes about the prince’s military exploits. Here he appears as an epic hero.

The combination of the emphatically religious and even more clearly expressed secular levels constitutes the distinctive style and originality of the Tale. In spite of this multiplicity of levels, however, and the apparently contradictory nature of the descriptions of Alexander, his character is unified. This unity is produced by the author’s attitude towards his hero, by the fact that for him Alexander is not only a heroic military commander, but also a wise statesman. For the enemies of the Russian land he is terrible and merciless: “the Moabite women” (meaning the Mongols here) frighten their children by saying “Alexander is coming!” But in his own land Alexander “judges orphans and widows righteously, gives alms, and is kind to his household”. He is the ideal prince, ruler and military leader.

In the episode of the battle on the Neva we are told of six heroes who fight alongside Alexander and distinguish themselves in battle. The first, Gavrilo Alexich, tried to ride on horseback onto an enemy boat, fell with his horse into the Neva, climbed out unharmed and went on fighting. The second, a Novgorodian called Zbyslav Yakunovich, slayed a vast number of the enemy with his battle axe. The third, Yakov from Polotsk, felled them with his sword. The fourth, Misha from Novgorod, sank three enemy ships. The fifth, “by the name of Sava from the younger bodyguard” “burst into the royal gold-canopied tent and hacked down the tent post”, which caused great rejoicing among Alexander’s men. The sixth, Ratmir, fought on foot and died “from many wounds”.

This story in the Tale is obviously based on a folk legend about the battle on the Neva, or perhaps an heroic song about the six brave men. The inclusion of such a story in a hagiographical text is explained by the heroic epic nature of this work. Nevertheless the hagiographical element is felt in this episode as well. The author merely lists the names of the heroes and mentions briefly, in one or two phrases, the feats of each of them.

The concluding section of the Tale, the account of the prince’s final days and death, is very solemn, yet full of sincere lyricism.

Alexander went to the Horde to see the khan in order to relieve Russians of the obligation of serving in the Mongol army. As already mentioned, he succeeded in this. After announcing that the prince fell sick on his way back from the Horde, the author gives vent to his feelings in exclamations of grief: “Oh, woe unto you, poor wretch! How can you describe your master’s death! How will your very eyes not fall out with tears! How will your heart not be torn from its roots! For a man can take leave of his father, but not of his good master. If it were possible, he would go into the grave with him.” After announcing the day on which Alexander died he quotes the words of Metropolitan Cyril and the men of Suzdal, when they heard the sad tidings: “And Metropolitan Cyril said: ‘My children, know that the sun has now set on the land of Suzdal!’ And the priests and deacons, monks, beggars, rich men and all folk exclaimed: ‘We are done for!”’

The Tale ends with an account of the “wondrous” and “memorable” miracle that was believed to have happened during the burial of the prince. When they were about to put a scroll with a prayer for absolution into the prince’s hand, the dead man “as if alive stretched out his hand and took the scroll from the metropolitan’s hand”.

In spite of the hagiographical nature of the work, the author makes extensive use of military epic legends and the poetic devices of military tales in his descriptions of the prince’s military feats. This enables him to reproduce in a hagiographical work the striking figure of the defender of the homeland, military leader and warrior. Right up to the sixteenth century The Tale of the Life of Alexander Nevsky was a kind of model for portraying Russian princes by describing their military feats.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature